- Design of Programming Languages and Interpreters

A programming language consists of a set of symbols, rules, and special words (keywords) that control the execution of a computer. The language is used to write programs that specify the behavior of a computer system. These programs are executed by a compiler or interpreter based on design of the language.

🗒 Fun Fact

Turing completeness is the ability for a system of instructions to simulate a Turing machine. A programming language that is Turing complete is theoretically capable of expressing all tasks accomplishable by computers.

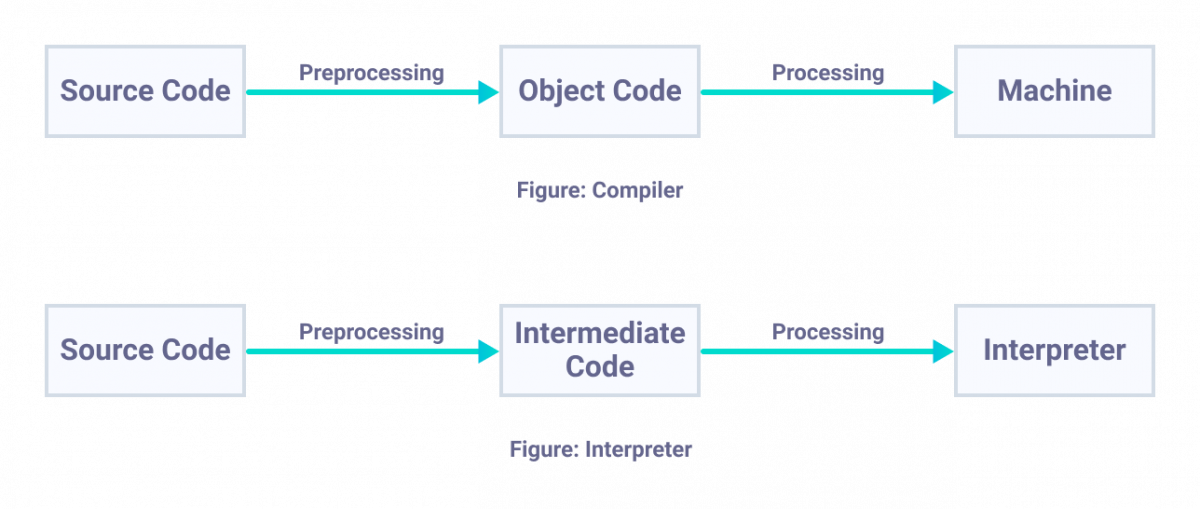

A compiler is a program that translates a source program written in some high-level programming language (such as Java) into machine code for some computer architecture (such as the Intel Pentium architecture). Another program with a similar mission is an interpreter. An interpreter differs from a compiler in that it does not generate a target program as an intermediate step. Instead, it directly executes the operations specified in the source program on inputs supplied by the user.

The key difference between a compiler and an interpreter is that a compiler translates the source code to generate a standalone machine code that can directly be executed by the operating system. On the other hand, an interpreter first converts the source code to an intermediate code and then the machine code is generated from this intermediate code.

🗒 Fun Fact

You can implement a compiler in any language, including the language it compiles this is called a self-hosting compiler.

The first step is lexical analysis. A lexer takes in a stream of characters/words and outputs a stream of tokens. A token is a group of characters that logically belong together, such as a keyword, an identifier, a number, or an operator. Some characters, such as whitespace and comments, are not represented by tokens. The lexer is also responsible for discarding these characters.

A parser takes in a stream of tokens and outputs a tree of nested data structures that represent the grammatical structure of the input. This tree is called an abstract syntax tree (AST). The parser is also responsible for detecting syntax errors and reporting them to the user.

At this point in the pipeline, individual charecteristics of the language come into play. The first bit of analysis is resolution of each identifier. This is where scope comes in the picture. A scope is a region of the program where a binding between a name and an entity holds. The resolution process is responsible for finding the entity that a name refers to. The second bit of analysis is type checking where in cases such as staticaly typed languages, the compiler checks if the types of the operands of an operator are compatible with the operator if not we report a TypeError.

All of this data gained from the performed analysis are stored in following manners:

- Nodes in the AST are annotated with the results of the analysis.

- The symbol table is updated with the results of the analysis with key being the name of the identifier and value being the entity it refers to.

At the end of the day our goal is that programmes written by programmers are executed by computers. But computers don't understand the language we write in. So we need to convert our language to a language that the computer understands. But another problem arises, there are many different types of computers and system architectures.

Say for example we want to write C++ and Java on x86 and ARM architectures. We can't write a compiler for each of these combinations. So we need to find a common language that we can convert our language to and then convert that language to the language of the computer. This common language is called intermediate representation (IR).

Hence a shared IR helps us to write one front end for each language and one back end for each target architecture. This is the reason why LLVM is so popular. LLVM is a collection of reusable compiler and toolchain technologies. It is designed to be modular and extensible. LLVM is written in C++ and is designed for compile-time, link-time, run-time, and "idle-time" optimization of programs written in arbitrary programming languages. Originally implemented for C/C++, the language-agnostic design of LLVM has since spawned a wide variety of front ends: languages with compilers that use LLVM include C#, Haskell, Java Bytecode, Ruby, Rust, Swift etc.

Once we have the IR we can perform optimizations on it since it is easier to perform optimizations on IR than on the source language and we understand what the user wants to do. There are many types of optimizations that can be performed on IR. Some of them are:

- Constant folding

int a = 2 + 3;

// After constant folding

int a = 5;- Dead code elimination

int foo() {

return 1;

return 2;

}

// After dead code elimination

int foo() {

return 1;

}- Common subexpression elimination

int foo() {

int a = 2 + 3;

int b = 2 + 3;

return a + b;

}

// After common subexpression elimination

int foo() {

int a = 2 + 3;

int b = a;

return a + b;

}🗒 Fun Fact

There are many more optimizations that can be performed on IR. You can read more about them here.

The final step is code generation. The code generator takes in the IR and outputs the target code. Now we have a decision to make wether we generate code for the system CPU or for a virtual machine. If we generate code for the system CPU then we need to generate code for each target architecture. If we generate code real machine code, we get an executable file that can be run directly on the target machine. If we generate code for a virtual machine, we get a bytecode file that can be run on a virtual machine. The virtual machine is responsible for executing the bytecode.

Languages like C and C++ generate code for the system CPU. Languages like Java and Python generate code for a virtual machine.

🗒 Fun Fact

Bytecode is known as portable code because it can be run on any machine that has a virtual machine for that bytecode also each instruction in the bytecode is often the same size one byte hence the name bytecode.

If your compiler produces bytecode your work still isn't finished. No chip speaks bytecode so you will need to translate it to a language a chip can understand. We have two options here:

- Write a Mini Compiler for each target architecture we want to support.

- This step is still simple as we are using the bytecode as an IR and we get to reuse the rest of the compiler pipeline we have already written.

- Write a Virtual Machine.

- We can write a program which emulates an idealized chip supporting our virtual architecture at runtime. The virtual machine is responsible for executing the bytecode. Advantage of this approach is simplicity and portability. Say we implement a VM in C now we can run our language on any machine that has a C compiler.

We finally have the user's program converted into a form the computer can understand now it's time to run it. If we converted the program to machine code we can run it directly on the CPU. If we converted the program to bytecode we can run it on the virtual machine.

In both cases we need to provide some runtime support. This includes things like memory management, garbage collection, and a standard library. The runtime support is written in the same language as the user's program. For example, if the user's program is written in C, the runtime support is also written in C.

The steps we took so far is the long route while most languages do walk the entire path, some languages take shortcuts. The following are some viable shortcuts:

- Single-pass compilers

- Tree-walk interpreters

- Transpilers

- JIT compilers (Just-in-time compilers)

A single-pass compiler is a compiler that does not perform multiple passes over the source code. Instead, it traverses the source code once and translates it to the target language. This means that the single-pass compiler must generate the target code as it reads the source code. This is in contrast to the multi-pass compilers we have seen so far, which read the entire source code before generating any target code. Single pass compilers attempt to produce target code in parsing step itself without building an intermediate representation.

Times when languages like PASCAL and C were designed, computers were slow and memory was expensive. So the designers of these languages wanted to make compilers that were fast and used less memory. So they designed single-pass compilers. It's why in C you can't call a function above the code where it is defined unless you have an explicit forward declaration.

🗒 Fun Fact

Syntax directed translation is a technique used by single-pass compilers. It is a method of writing compilers where the grammar of the source language is augmented with embedded actions which add semantic information to the parse tree and ultimately generate code for the target language.

A tree-walk interpreter is a compiler that does not generate any target code. Instead, it walks the abstract syntax tree and interprets the semantics of the source code. This is in contrast to the compilers we have seen so far, which generate target code from the abstract syntax tree. Tree-walk interpreters are also known as recursive-descent interpreters.

Attempting write a complete back end for a language can be tedious. But what if we treated another language similar in level to yours as your intermediate representation. Going further you can target existing compilers and toolchains for that source language.

After spread and rise of UNIX machines it began a trend of writing compilers for high level languages that targeted C as the intermediate representation. This is called transpiling. The most famous example of this is the CPython interpreter. CPython is a Python interpreter written in C. It converts Python code to C code and then compiles it using the C compiler.

The main phase of difference from traditional compilers are in the code generation phase. Instead of generating machine code, transpilers generate code in another high-level language. This code is then compiled by another compiler.

A JIT compiler is a compiler that generates target code at runtime. This is less recommended as it is less of a shortcut and more of a hack. Fastest method to execute code is to run it directly on the CPU. But if we want to run code on the CPU, we need to generate machine code. The JIT compiler compiles user code to native code for the specific computer architecture either using platform independent bytecode or by compiling from source code. The JIT compiler then executes the native code.

| Compiler | Interpreter |

|---|---|

| Converts the entire source code to usually lower level code | Converts the source code line by line to machine code |

| Faster than interpreter | Slower than compiler |

| Takes more memory | Takes less memory |

| Generates intermediate object code | No intermediate object code is generated |

| Examples: C, C++, Java, etc. | Examples: Python, Ruby, etc. |

You can check out the progress of the project here.

<style> .btn-blue { background-color: #3498db; border-color: #3498db; color: #fff; padding: 10px 20px; border-radius: 5px; text-decoration: none; } .btn-blue:hover { background-color: #2980b9; border-color: #2980b9; color: #fff; } </style> Next: Lox Language