- React

- React

- React General Resources

- React Community

- React Online Playgrounds

- Another Awesome Lists

- React Tutorials

- React General Tutorials

- React Hooks

- React and TypeScript

- React Performance

- React Internals

- React Interview Questions

- React Tools

- React Development Tools

- React Starter Kits and Toolchains

- React Frameworks

- React Styling

- React Routing

- React Component Libraries

- React Awesome Components

- React Testing

- React Libraries

- React Integration

- React State Management

- React AR and VR

- React Renderers

- Forms

- Autocomplete

- Graphics

- Data Managing

- Maps

- Charts

- React Native

- React Native General Resources

- React Native Tutorials

- React Native Development Tools

- React Native Sample Apps

- React Native Boilerplates

- React Native Awesome Components

- React Native Libraries

- Redux

- Redux General Resources

- Redux Tools

- Redux Tutorials

- GraphQL

- GraphQL General Resources

- GraphQL Tools

- GraphQL Tutorials

- GraphQL Implementations

- Database Integration

- Relay

- Relay General Resources

- Relay Tutorials

- Relay Tools

- Videos

- reactjsvideos.com

- Important Talks

- React.js Conf 2015 Playlist

- ReactEurope Conf 2015 Day 1 Playlist

- ReactEurope Conf 2015 Day 2 Playlist

- ReactRally Conf 2015 Playlist

- React.js Conf 2016 Playlist

- React Amsterdam 2016 Playlist

- ReactEurope Conf 2016 Day 1 Playlist

- ReactEurope Conf 2016 Day 2 Playlist

- ReactRally Conf 2016 Playlist

- React Conf 2017 Playlist

- React.js Amsterdam 2018 Playlist

- React Amsterdam 2019 Playlist

- Video Tutorials

- Demo React Apps

- Real React Apps

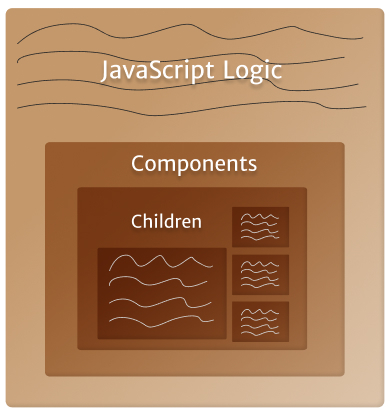

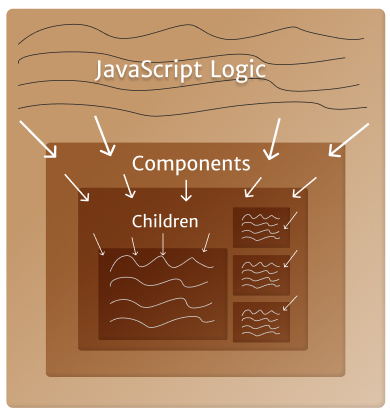

- React Overview:

- Hello World

- The smallest React example looks like this:

- How to Read This Guide

- Knowledge Level Assumptions

- Introducing JSX

- Consider this variable declaration:

- Why JSX?

- Embedding Expressions in JSX

- JSX is an Expression Too

- Specifying Attributes with JSX

- Specifying Children with JSX

- JSX Prevents Injection Attacks

- JSX Represents Objects

- Rendering Elements

- Elements are the smallest building blocks of React apps.

- Rendering an Element into the DOM

- Updating the Rendered Element

- React Only Updates What's Necessary

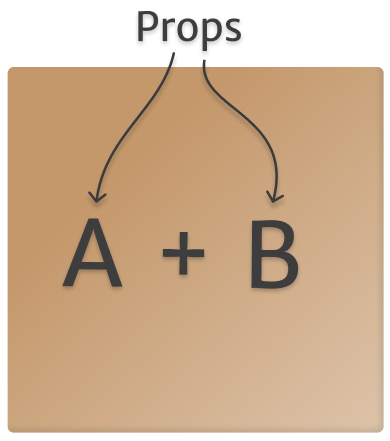

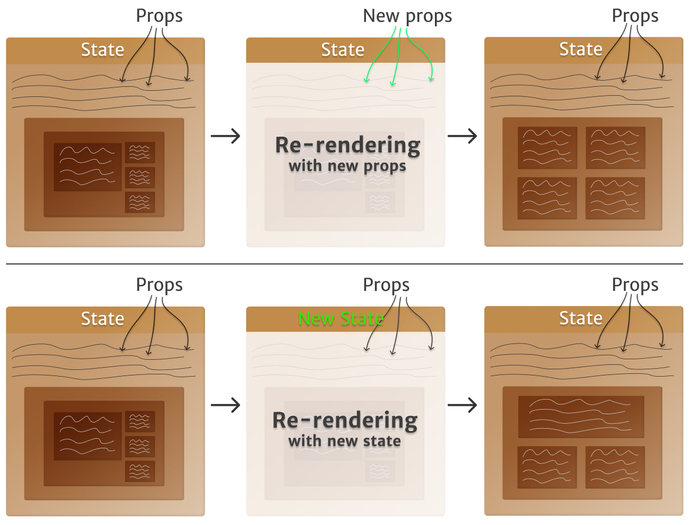

- Components and Props

- Components let you split the UI into independent, reusable pieces, and think about each piece in isolation. This page provides an introduction to the idea of components. You can find a detailed component API reference here.

- Function and Class Components

- Rendering a Component

- Composing Components

- Extracting Components

- Props are Read-Only

- State and Lifecycle

- This page introduces the concept of state and lifecycle in a React component. You can find a detailed component API reference here.

- Converting a Function to a Class

- Adding Local State to a Class

- Adding Lifecycle Methods to a Class

- Using State Correctly

- Do Not Modify State Directly

- State Updates May Be Asynchronous

- State Updates are Merged

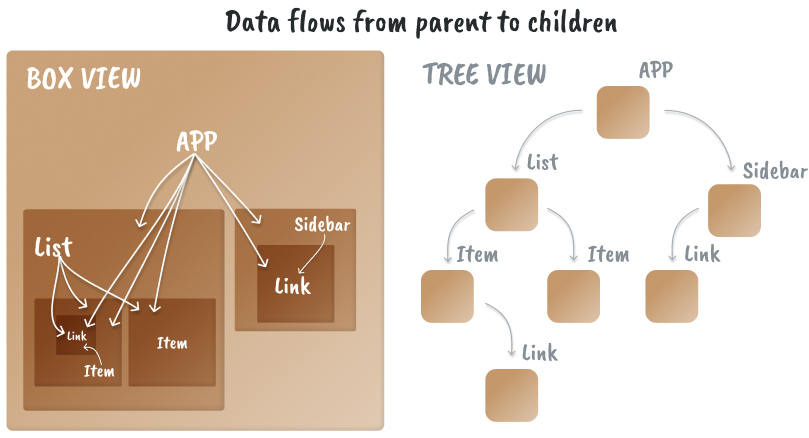

- The Data Flows Down

- Handling Events

- Handling events with React elements is very similar to handling events on DOM elements. There are some syntax differences:

- Passing Arguments to Event Handlers

- Conditional Rendering

- In React, you can create distinct components that encapsulate behavior you need. Then, you can render only some of them, depending on the state of your application.

- Element Variables

- Inline If with Logical && Operator

- Inline If-Else with Conditional Operator

- Preventing Component from Rendering

- Lists and Keys

- First, let's review how you transform lists in JavaScript.

- Rendering Multiple Components

- Basic List Component

- Keys

- Extracting Components with Keys

- Keys Must Only Be Unique Among Siblings

- Embedding map() in JSX

- Forms

- HTML form elements work a bit differently from other DOM elements in React, because form elements naturally keep some internal state. For example, this form in plain HTML accepts a single name:

- Controlled Components

- The textarea Tag

- The select Tag

- The file input Tag

- Handling Multiple Inputs

- Controlled Input Null Value

- Alternatives to Controlled Components

- Fully-Fledged Solutions

- Lifting State Up

- Often, several components need to reflect the same changing data. We recommend lifting the shared state up to their closest common ancestor. Let's see how this works in action.

- Adding a Second Input

- Writing Conversion Functions

- Lifting State Up

- Lessons Learned

- Composition vs Inheritance

- React has a powerful composition model, and we recommend using composition instead of inheritance to reuse code between components.

- Containment

- Specialization

- So What About Inheritance?

- Thinking in React

- React is, in our opinion, the premier way to build big, fast Web apps with JavaScript. It has scaled very well for us at Facebook and Instagram.

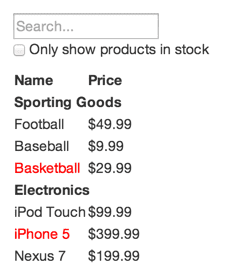

- Start With A Mock

- Step 1: Break The UI Into A Component Hierarchy

- Step 2: Build A Static Version in React

- A Brief Interlude: Props vs State

- Step 3: Identify The Minimal (but complete) Representation Of UI State

- Step 4: Identify Where Your State Should Live

- Step 5: Add Inverse Data Flow

- And That's It

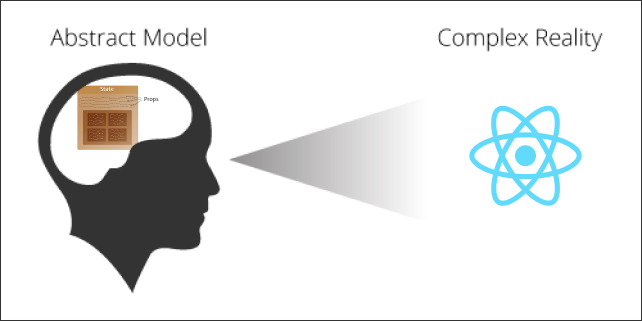

- A visual guide to React Mental models

- the-rendering-mental-model-understanding-reacts-magic

JavaScript Library for building User Interfaces

- React Official Tutorial

- Using React in Visual Studio Code

- Scrimba - Learn React for free interactively

- FreeCodeCamp React Challenges

- React Cheatsheet

- React Patterns

- Setup Flow with React

- React Hooks

- Awesome React Hooks

- Thinking in React Hooks

- Replacing Redux with React Hooks and Context

- React Hooks cheat sheet: Unlock solutions to common problems

- How to fetch data with React Hooks?

- Easy to understand React Hook recipes

- React Hooks Video Tutorial

- TypeScript, React and Webpack

- JSX in TypeScript

- Cheatsheets for experienced React developers getting started with TypeScript

- React by Example

- React Optimizing Performance

- Introducing the React Profiler

- Optimizing React: Virtual DOM explained

- A Definitive Guide to Optimize Major Performance issues in React

- Twitter Lite and High Performance React Progressive Web Apps at Scale

- Using the React DevTools Profiler to Diagnose React App Performance Issues

- Top 5 Practices to Boost React Performance

- React is Slow, React is Fast: Optimizing react Apps in Practice

- Rendering large lists with react-window

- Reconciliation

- React Fiber Architecture

- Build your own React

- Inside Fiber: In-depth overview of the new reconciliation algorithm in React

- Entire React code base explanation by visual block schemes

- 13 Essential React Interview Questions

- List of React interview Questions and Answers

- React Coding Challenges

- react-devtools - Inspection of React component hierarchy in the Chrome and Firefox Developer Tools

- react-hot-loader - Tweak React components in real time

- react-loadable - A higher order component for loading components with promises

- loadable-components - React code splitting made easy

- reactotron - A desktop app for inspecting your React and React Native projects

- storybook - UI component dev & test

- docz - Zero Config, live-reloading documentation with Markdown + JSX

- react-styleguidist - Isolated React component development environment with a living style guide

- react-cosmos - Dev tool for creating reusable React components

- eslint-plugin-react - React specific linting rules for ESLint

- eslint-plugin-jsx-a11y - Static AST checker for a11y rules on JSX elements

- @axe-core/react - Accessibility auditing for React applications

- DataFormsJS JSX Loader - Small JavaScript Compiler for quickly converting JSX to JS directly on a web page

- Why Did You Render - Monkey patches React to notify you about avoidable re-renders.

- Divjoy - React codebase and UI generator to speed up development (paid)

- Plasmic - Powerful design tool for building your React components visually.

- create-react-app - Set up a modern Web app by running one command

- Razzle - Build production ready React applications. Razzle is toolchain for modern static and dynamic websites and web applications

- Neutrino React Preset -

@neutrinojs/reactis a Neutrino preset that supports building React web applications - react-starter-kit - Isomorphic Web app boilerplate

- create-react-library - CLI for creating reusable, modern React libraries using Rollup and create-react-app.

- tsdx - Zero-config CLI for TypeScript package development

- next.js - The React Framework

- gatsby.js - Free and open source framework based on React

- react-admin - Frontend Framework for building B2B applications on top of REST/GraphQL APIs

- remix - Finally, a killer React framework from the creators of React Router

- Blitz - The Fullstack React Framework

- aleph.js - The React Framework in Deno

- styled-components - Visual primitives for the component age

- emotion - Library designed for writing CSS styles with JavaScript

- radium - A toolchain for React component styling

- jss - Authoring tool for CSS

- aphrodite - Framework-agnostic CSS-in-JS with support for server-side rendering, browser prefixing, and minimum CSS generation

- react-router - Declarative routing for React

- navi - Declarative, asynchronous routing for React

- curi - JavaScript router for single-page applications

- reach - Next Generation Routing for React

- universal-router - A simple middleware-style router for isomorphic JavaScript web apps

- wouter - A minimalist-friendly ~1.3KB routing library

- material-ui - React components for faster and easier web development

- blueprint - A React-based UI toolkit for the webs

- Fluent UI - A set of React components for building Microsoft web experiences

- react-bootstrap - Bootstrap components built with React

- reactstrap - Simple React Bootstrap 4 components

- ant-design - A design system with values of Nature and Determinacy

- chakra-ui - Simple, Modular & Accessible UI Components for your React Applications

- semantic-ui-react - The official Semantic-UI-React integration

- evergreen - Evergreen React UI Framework by Segment

- grommet - A react-based framework that provides accessibility, modularity, responsiveness, and theming in a tidy package

- rebass - React primitive UI components built with styled-system

- reakit - Accessible, Composable and Customizable components for React

- rsuite - A suite of React components

- atlaskit - Atlassian's official UI library, built according to the Atlassian Design Guidelines.

- baseweb - Base Web is a foundation for initiating, evolving, and unifying web products.

- primereact - A complete UI Framework for React with 50+ components featuring material, bootstrap and custom themes.

- eui - Elastic UI Framework

- react-spectrum - Adobe's collection of libraries and tools that help you build adaptive, accessible, and robust user experiences

- ring-ui - JetBrains Web UI components

- react-bulma-components - React components for Bulma framework

- react-bulma - React.js components for Modern CSS framework based on Flexbox

- trunx - Super Saiyan React components, son of awesome Bulma, implemented in TypeScript

- bumbag-ui - Build accessible & themeable React applications with your Bumbag

- Awesome React Components list

- react-select - The Select Component for React

- react-beautiful-dnd - Beautiful and accessible drag and drop for lists with React

- react-dnd - Drag and Drop for React

- react-grid-layout - A draggable and resizable grid layout with responsive breakpoints

- react-table - A lightweight, fast and extendable datagrid for React

- react-data-grid - Excel-like grid component built with React

- react-draggable - React draggable component

- react-resizable-and-movable - A resizable and draggable component for React

- react-resizable - A simple React component that is resizable with a handle

- react-resizable-box - A resizable component for React

- react-searchbox-awesome - Minimalistic searchbox

- react-sortable-pane - A sortable and resizable pane component for React

- react-spaces - Nestable resizable, anchored, scrollable components

- react-dates - An easily internationalizable, mobile-friendly datepicker library for the web

- react-big-calendar - Calendar component

- react-datepicker - ReactJS Datepicker

- react-list - A versatile infinite scroll React component

- react-intl - Internationalize React apps

- react-i18next - Internationalization for React done right

- react-aria-modal - A fully accessible React modal

- react-hotkeys - Declarative hotkey and focus area management for React

- react-keydown - Lightweight keydown wrapper for React components

- react-joyride - Create guided tours for your apps

- react-virtualized - React components for efficiently rendering large lists and tabular data

- react-window - React components for efficiently rendering large lists and tabular data

- react-text-mask - Input mask for React

- react-loading-skeleton - Create skeleton screens that automatically adapt to your app

- react-spinkit - A collection of loading indicators animated with CSS for React

- rheostat - Accessible slider component built with React

- qrcode.react - QR component for use with React

- react-archer - Draw arrows between React elements

- react-pdf-viewer - A PDF viewer made for React

- react-parallax-tilt - Easily apply tilt hover effect on React components

- react-popper - Position tooltips and popovers in an elegant, performant manner

- react-tsparticles - Easily create highly customizable particles animations

- react-spring - Spring-physics based animation library for React applications

- framer-motion - A React library to power production-ready animations

- react-accessible-accordion - React Component for creating an 'Accordion' that adheres to the WAI ARIA spec for accessibility.

- react-truncate-markup - React component for truncating JSX markup.

- react-cookie - Universal cookies for React

- react-slick - Carousel component built with React

- react-gtm-module - Google Tag Manager Module for React

- react-device-detect - Detect device for React

- react-colorful - A tiny (2,5 KB), dependency-free, fast and accessible color picker component

- react-modal - Accessible modal dialog component for React

- cleave.js - Format input text content when you are typing

- react-fontawesome - Font Awesome 5 React component

- jest - Delightful JavaScript Testing Framework

- enzyme - JavaScript Testing utilities for React

- react-testing-library - Simple and complete React DOM testing utilities

- react-hooks-testing-library - React hooks testing utilities that encourage good testing practices

- majestic - Zero config GUI for Jest

- react-border-wrapper - A wrapper for placing elements along div borders in React.

- react-magic - Automatically AJAXify plain HTML with the power of React

- react-toolbox - A set of React components implementing Google's Material Design specification

- tcomb-react - Library allowing you to check all the props of your React components

- react-responsive - Media queries in react for responsive design

- preact - Fast 3kb React alternative with the same ES6 API.

- riotjs - A React-like, 3.5KB user interface library

- Maple.js - Bringing the concept of web-components to React

- react-i13n - A performant, scalable and pluggable approach to instrumenting your React application

- react-icons - svg react icons of popular icon packs

- react-open-doodles - Awesome free illustrations as react components.

- Keo - Plain functions for a more functional Deku approach to creating React components, with functional goodies such as pipe, memoize, etc...

- Bit - A virtual repository for managing and using react and other web components across applications

- AtlasKit - Atlassian's React UI library

- ReactiveSearch - UI components library for Elasticsearch

- Slate - A completely customizable framework for building rich text editors.

- react-json-schema - Construct React elements from JSON by mapping JSON definitions to React components that you expose.

- react-lodash - Lodash as React components

- react-helmet - A document head manager for React

- react-snap - Zero-configuration framework-agnostic static prerendering for SPAs

- Draft.js - A React framework for building text editors

- refract - Harness the power of reactive programming to supercharge your components

- react-desktop - OS X and Windows UI components built with React

- reapop - A simple and customizable React notifications system

- react-extras - Useful components and utilities for working with React

- react-instantsearch - Lightning-fast search for React and React Native applications, by Algolia

- uppy - The next open source file uploader for web browsers

- react-motion - A spring that solves your animation problems

- react-esi - React Edge Side Includes

- react-aria - Adobe's library of React Hooks that provides accessible UI primitives for your design system

- react-uploady - Modern file-upload components & hooks for React.

- ReasonReact

- React Rails

- ReactJS.NET

- om - ClojureScript interface

- Reagent - A minimalistic ClojureScript interface to React.js

- Express React views

- React Page Middleware

- ngReact - React Components in Angular

- coffee-react-transform - Provides React JSX support for Coffeescript

- sprockets-coffee-react - Sprockets preprocessor for CJSX

- react-kup - A simple, non-intrusive alternative to jsx for coffeescript

- turbo-react - Combine Turbolinks and React to apply DOM diffs

- react-bacon - A little module for using React with Bacon.js

- msx - React's JSX Transformer, tweaked to output calls to Mithril

- react-backbone - Backbone-aware mixins for react

- NestedReact - transparent integration with Backbone Views and NestedTypes models

- backbone-reaction - React, Backbone and then some

- react.backbone - Plugin for React to make Backbone migration easier

- reactbone - React extensions for Backbone

- backbone-react-ui - React components for use with backbone and backbone paginator

- react-events - Declarative managed event bindings for react components

- react-mixin-manager - React mixin registration manager

- react-topcoat by @plaxdan - Topcoat CSS components built with the React library

- react-topcoat by @arnemart - A collection of React components for Topcoat

- reactdown - Write React components using markdown syntax

- react-jade - Compile Jade to React JavaScript

- jade-react - Compile Jade templates to React.DOM expressions

- gulp-jade-react - Compile Jade templates into React de-sugared JSX with Gulp

- sbt-reactjs - React SBT Plugin using npm

- scalajs-react - A guilty affair between Scala.js and Facebook's React

- react-xtags - Using React to implement xtags

- jreact - React on server-side Java (with Rhino or Nashorn)

- React.hiccup - A complete replacement for JSX written in sweet.js

- react-play - Rendering React components in the Play Framework with JDK8's Nashorn

- rx-react - Utilities to works with React in a RxJS

- react-with-di - A hacked prototype of React.js with DI

- reactfire - ReactJS mixin for easy Firebase integration

- react-clickdrag-mixin - ClickDrag mixin for React component

- react-masonry-mixin - Standalone mixin for Masonry (@desandro)

- react-packery-mixin - Standalone mixin for Packery (Metafizzy)

- react-dropzone - Simple HTML5 drag-drop zone with React.js.

- aframe-react - A-Frame VR + React

- react-three-fiber - A react reconciler for threejs (web and react-native)

- react-three - React bindings to create and control a 3D scene using three.js

- react-three-renderer - Render into a three.js canvas using React

- react-threejs - Simplest bindings between React & Three.js

- react-masonry-css - Fast Masonry layout powered by CSS, dependency free

- react-captcha - A react.js reCAPTCHA for Google

- reaptcha - Clean, modern and simple React wrapper for Google reCAPTCHA

- react-recaptcha-that-works - A reCAPTCHA bridge for React that works

- redux - Predictable State Container for JavaScript Apps

- mobx - Simple, scalable state management

- react-query

- flux - Application architecture for building user interfaces

- recoil - Experimental state management library for React apps

- xstate-react - State machines and statecharts for the modern web

- zustand - Bear necessities for state management in React

- easy-peasy - Vegetarian friendly state for React

- hookstate - The simple but very powerful and incredibly fast state management for React that is based on hooks

- effector - Fast and powerful reactive state manager

- reactn - React, but with built-in global state management

- Viro React - Platform for rapidly building AR/VR applications using React Native

- react-three-fiber - A React renderer for Three.js

- react-pdf - Create PDF files using React

- ink - React for interactive command-line apps

- react-blessed - A React renderer for blessed terminal interface library

- react-sketchapp - Render React components to Sketch

- react-figma - A React renderer for Figma

- react-nil - A react null renderer

- remotion - Create videos programmatically in React

- formik - Build forms in React, without the tears

- react-hook-form - React Hooks for forms validation

- react-jsonschema-form - A React component for building Web forms from JSON Schema

- react-final-form - High performance subscription-based form state management for React

- unform - Performance-focused API for React forms

- formily - Alibaba Group Unified Form Solution

- uniforms - A React library for building forms from any schema

- formsy-react - A form input builder and validator for React

- react-formal - Sophisticated HTML form management for React

- react-autocomplete by @rackt - WAI-ARIA compliant React autocomplete (Archived, read-only)

- react-autosuggest by @moroshko - WAI-ARIA compliant React autosuggest component

- react-autocomplete by @eliseumds - Just tasting some ReactJS + RxJS

- react-autocomplete by @prometheusresearch - Autocomplete widget based on React

- instatype by @gragland - Simple react autocomplete component

- downshift - 🏎 Primitives to build simple, flexible, WAI-ARIA compliant enhanced input React components

- React Bootstrap Typeahead - A React-based typeahead that relies on Bootstrap for styling and was originally inspired by Twitter's typeahead.js.

- react-art - React Bridge to the ART Drawing Library

- react-canvas - High performance

<canvas>rendering for React components - react-famous - Complex 3D animations UI at 60 FPS with Famo.us

- react-kinetic - HTML5 Canvas via KineticJS using React

- react-svg-morph - morph your svg components one into another

- react-hooks-svgdrawing - SVG Drawing with React hooks

- react-svg-pan-zoom - A React component that adds pan and zoom features to SVG.

- immer - Create the next immutable state by mutating the current one

- ReSub - A library for writing better React components and data stores

- immutable-js - Immutable Data Collections for Javascript

- baobab - JavaScript & TypeScript persistent and optionally immutable data tree with cursors

- WatermelonDB - 🍉 Reactive & asynchronous database for powerful React and React Native apps ⚡️

- RxDB - A realtime Database for JavaScript Applications

- react-googlemaps - React interface to Google maps

- react-maps - A map component for React

- react-google-maps - React.js Google Maps integration component

- react-gmaps - A Google Maps component for React.js

- react-map-gl - A React wrapper for MapboxGL-js plus overlay API

- google-map-react - Isomorphic google map React component

- react-mapbox-gl - A mapbox-gl-js wrapper to make the API react friendly

- google-maps-react - A declarative Google Map React component using React, lazy-loading dependencies, current-location finder and a test-driven approach by the Fullstack React team.

- react-leaflet - React components for Leaflet maps

- react-geo - A set of geo-related components using react, antd, and ol

- pigeon-maps - ReactJS maps without external dependencies

- vx - Visualization components

- victory - A collection of composable React components for building interactive data visualizations

- react-vis - Data Visualization Components

- recharts - Redefined chart library built with React and D3

- nivo - Provides a rich set of data visualization components, built on top of the D3 and React libraries

- echarts-for-react - Apache ECharts components for React wrapper

- react-apexcharts - React Component for ApexCharts

- chartify - React plugin for building charts using CSS

Framework for building native apps using React

- React Native Official Site

- React Native GitHub

- React Native Newsletter

- React Native Playground

- React Native Awesome List

- React Native StackOverflow

- React Native Radio

- React Native Tutorial

- Introducing React Native: Building Apps with JavaScript

- Introduction to React Native: Building iOS Apps with JavaScript

- React Native Meets Async Functions

- Digital Smart Mirror lab with React Native

- The Beauty Of React Native: Building Your First iOS App With JavaScript (Part 1)

- The Beauty Of React Native: Building Your First iOS App With JavaScript (Part 2)

- A Mini-Course on React Native Flexbox

- A Complete Guide to Flexbox

- Test driving react native applications

- Using React Native With TypeScript

- react-native-code-push - React Native module for CodePush

- Create React Native App - Create React Native apps that run on iOS, Android, and web

- Ignite - The hottest CLI for React Native, boilerplates, plugins, generators, and more!

- Expo - The Expo platform for making cross-platform mobile apps

- react-navigation - Routing and navigation for your React Native apps

- react-native-social-share - Use the iOS and Android native Twitter and Facebook share popup with React Native

- react-native-fbsdk - A wrapper around the iOS Facebook SDK

- react-native-side-menu - Simple customizable component to create side menu

- react-native-mapbox-gl - A Mapbox GL react native module

- react-native-icons - Quick and easy icons in React Native

- react-native-vector-icons - 3000 Customizable Icons for React Native with support for NavBar/TabBar

- react-native-google-signin - Google Signin for React Native

- react-native-picker-modal-view

- react-native-gifted-chat - The most complete chat UI for React Native

- react-native-fast-image - FastImage, performant React Native image component

- recyclerlistview - High performance listview for React Native and web!

- react-native-largelist - The best large list component for React Native

- react-native-gesture-handler - Declarative API exposing platform native touch and gesture system to React Native

- rn-placeholder - Display some placeholder stuff before rendering your text or media content in React Native

- sentry-react-native - Real-time crash reporting for your web apps, mobile apps, and games.

- realm-js - Realm is a mobile database: an alternative to SQLite & key-value stores

- react-native-device-info - Device Information for React Native iOS and Android

- react-native-react-bridge - A toolset to run React web app in React Native and handle communication between them.

- uncompress-react-native - Simple library to decompress files .zip, .rar, .cbz, .cbr in React Native.

Predictable State Container for JavaScript Apps

- react-redux - Official React bindings for Redux

- redux-toolkit - The official, opinionated, batteries-included toolset for efficient Redux development

- redux-devtools - DevTools for Redux with hot reloading, action replay, and customizable UI

- reselect - Selector library for Redux

- redux-thunk - Thunk middleware for redux

- redux-saga - An alternative side effect model for Redux apps

- connected-react-router - A Redux binding for React Router

- redux-form - A Higher Order Component using react-redux to keep form state

- normalizr - Normalizes nested JSON according to a schema

- redux-observable - RxJS middleware for Redux

- redux-undo - Higher order reducer to add undo/redo functionality to redux state containers

- redux-persist - Persist and rehydrate a redux store

- Redux Essentials

- Redux Fundamentals

- Fundamentals of Redux Course from Dan Abramov

- Building React Applications with Idiomatic Redux

A query language for your API

- graphql-js - A reference implementation of GraphQL for JavaScript

- express-graphql - Create a GraphQL HTTP server with Express

- Apollo - Industry-standard GraphQL implementation

- GraphQL Playground - GraphQL IDE for better development workflows

- graphql-ruby - Ruby implementation of GraphQL

- graphql-java - GraphQL Java implementation

- sangria - Scala GraphQL client and server library

- graphql-php - A PHP port of GraphQL reference implementation

- graphene - GraphQL framework for Python

- graphql-dotnet - GraphQL for .NET

- graphql-go - GraphQL for Go

- juniper - GraphQL server library for Rust

- Hasura - Instant GraphQL for all your data

- Prisma - Next-generation ORM for Node.js and TypeScript

- graphql-sequelize - GraphQL & Relay for MySQL & Postgres via Sequelize

Data-Driven React Applications

- Official Relay Getting Started

- Relay for Visual Learners

- Getting Started with Relay

- Relay and Routing

- graphql-relay-js - A library to help construct a graphql-js server supporting react-relay

- react-router-relay - Relay integration for React Router

- relay-local-schema - Use Relay without a GraphQL server

- relay-codemod - Codemod scripts based for on jsodeshift to update Relay APIs

- Pete Hunt: React: Rethinking best practices - JSConf EU 2013

- Pete Hunt: React: Rethinking Best Practices (updated) - JSConf.Asia 2013

- Tom Occhino and Jordan Walke: JS Apps at Facebook - JSConfUS 2013

- React: CSS in JS

- Pete Hunt: Be Predictable, Not Correct - Mountain West JavaScript 2014

- Hacker Way: Rethinking Web App Development at Facebook

- Christopher Chedeau: Why does React Scale? - JSConf2014

- Christopher Chedeau: React's Architecture - OSCON 2014

- Pete Hunt: React RESTful UI Rendering - Strange Loop 2014

- Pete Hunt: How Instagram.com Works - OSCON 2014

- Bill Fisher and Jing Chen: React and Flux - NewCircle Training 2014

- Sebastian Markbage: Minimal API Surface Area - JSConf EU 2014

- Avik Chaudhuri: JavaScript Testing and Static Type Systems at Scale - Scale 2014

- React Native & Relay: Bringing Modern Web Techniques to Mobile - f8 2015)

- Citrusbyte Presents GraphQL: A Horizontal Platform with Nick Schrock

- Laney Kuenzel: Mutations and Subscriptions in Relay - JSConf 2015

- React Today and Tomorrow and 90% Cleaner React With Hooks - React Conf 2018

- React Conferences

- React Videos

- Awesome React Talks

- hackernews-react-graphql - Hacker News clone rewritten with universal JavaScript, using React and GraphQL

- react-reduction - Free Admin Template Built with React and Bootstrap4

- reactjs-tmdb-app - Responsive React The Movie Database App

- react-shopping-cart - Simple ecommerce cart application built with React Redux

- kibana - Your window into the Elastic Stack

- firefox debugger - The Firefox debugger that works anywhere

- spectrum – Simple, powerful online communities

- mattermost - Open source Slack alternative

- overreacted - Personal blog by Dan Abramov

- winamp2-js - Winamp 2 reimplemented for the browser

- dnote - A command line notebook with multi-device sync and web interface

ReactDOM.render(

<h1>Hello, world!</h1>,

document.getElementById('root')

);

It displays a heading saying "Hello, world!" on the page.

https://codepen.io/bgoonz/pen/wveBJBM

Click the link above to open an online editor. Feel free to make some changes, and see how they affect the output. Most pages in this guide will have editable examples like this one.

In this guide, we will examine the building blocks of React apps: elements and components. Once you master them, you can create complex apps from small reusable pieces.

TipThis guide is designed for people who prefer learning concepts step by step. If you prefer to learn by doing, check out our practical tutorial. You might find this guide and the tutorial complementary to each other.

This is the first chapter in a step-by-step guide about main React concepts. You can find a list of all its chapters in the navigation sidebar. If you're reading this from a mobile device, you can access the navigation by pressing the button in the bottom right corner of your screen.

Every chapter in this guide builds on the knowledge introduced in earlier chapters. You can learn most of React by reading the "Main Concepts" guide chapters in the order they appear in the sidebar. For example, "Introducing JSX" is the next chapter after this one.

React is a JavaScript library, and so we'll assume you have a basic understanding of the JavaScript language. If you don't feel very confident, we recommend going through a JavaScript tutorial to check your knowledge level and enable you to follow along this guide without getting lost. It might take you between 30 minutes and an hour, but as a result you won't have to feel like you're learning both React and JavaScript at the same time.

NoteThis guide occasionally uses some newer JavaScript syntax in the examples. If you haven't worked with JavaScript in the last few years, these three points should get you most of the way.

const element = <h1>Hello, world!</h1>;

This funny tag syntax is neither a string nor HTML.

It is called JSX, and it is a syntax extension to JavaScript. We recommend using it with React to describe what the UI should look like. JSX may remind you of a template language, but it comes with the full power of JavaScript.

JSX produces React "elements". We will explore rendering them to the DOM in the next section. Below, you can find the basics of JSX necessary to get you started.

React embraces the fact that rendering logic is inherently coupled with other UI logic: how events are handled, how the state changes over time, and how the data is prepared for display.

Instead of artificially separating technologies by putting markup and logic in separate files, React separates concerns with loosely coupled units called "components" that contain both. We will come back to components in a further section, but if you're not yet comfortable putting markup in JS, this talk might convince you otherwise.

React doesn't require using JSX, but most people find it helpful as a visual aid when working with UI inside the JavaScript code. It also allows React to show more useful error and warning messages.

With that out of the way, let's get started!

In the example below, we declare a variable called name and then use it inside JSX by wrapping it in curly braces:

const name = 'Josh Perez';const element = <h1>Hello, {name}</h1>;

ReactDOM.render(

element,

document.getElementById('root')

);

You can put any valid JavaScript expression inside the curly braces in JSX. For example, 2 + 2, user.firstName, or formatName(user) are all valid JavaScript expressions.

In the example below, we embed the result of calling a JavaScript function, formatName(user), into an <h1> element.

function formatName(user) {

return user.firstName + ' ' + user.lastName;

}

const user = {

firstName: 'Harper',

lastName: 'Perez'

};

const element = (

<h1> Hello, {formatName(user)}! </h1>);

ReactDOM.render(

element,

document.getElementById('root')

);

https://codepen.io/bgoonz/pen/oNwgZgm

We split JSX over multiple lines for readability. While it isn't required, when doing this, we also recommend wrapping it in parentheses to avoid the pitfalls of automatic semicolon insertion.

After compilation, JSX expressions become regular JavaScript function calls and evaluate to JavaScript objects.

This means that you can use JSX inside of if statements and for loops, assign it to variables, accept it as arguments, and return it from functions:

function getGreeting(user) {

if (user) {

return <h1>Hello, {formatName(user)}!</h1>; }

return <h1>Hello, Stranger.</h1>;}

You may use quotes to specify string literals as attributes:

const element = <div tabIndex="0"></div>;

You may also use curly braces to embed a JavaScript expression in an attribute:

const element = <img src={user.avatarUrl}></img>;

Don't put quotes around curly braces when embedding a JavaScript expression in an attribute. You should either use quotes (for string values) or curly braces (for expressions), but not both in the same attribute.

Warning:Since JSX is closer to JavaScript than to HTML, React DOM uses camelCase property naming convention instead of HTML attribute names.For example, class becomes className in JSX, and tabindex becomes tabIndex.

If a tag is empty, you may close it immediately with />, like XML:

const element = <img src={user.avatarUrl} />;

JSX tags may contain children:

const element = (

<div>

<h1>Hello!</h1>

<h2>Good to see you here.</h2>

</div>);

It is safe to embed user input in JSX:

const title = response.potentiallyMaliciousInput;

// This is safe:

const element = <h1>{title}</h1>;

By default, React DOM escapes any values embedded in JSX before rendering them. Thus it ensures that you can never inject anything that's not explicitly written in your application. Everything is converted to a string before being rendered. This helps prevent XSS (cross-site-scripting) attacks.

Babel compiles JSX down to React.createElement() calls.

These two examples are identical:

const element = (

<h1 className="greeting">

Hello, world!

</h1>);

const element = React.createElement(

'h1',

{className: 'greeting'},

'Hello, world!'

);

React.createElement() performs a few checks to help you write bug-free code but essentially it creates an object like this:

// Note: this structure is simplified

const element = {

type: 'h1',

props: {

className: 'greeting',

children: 'Hello, world!'

}

};

These objects are called "React elements". You can think of them as descriptions of what you want to see on the screen. React reads these objects and uses them to construct the DOM and keep it up to date.

We will explore rendering React elements to the DOM in the next section.

Tip:We recommend using the "Babel" language definition for your editor of choice so that both ES6 and JSX code is properly highlighted.

An element describes what you want to see on the screen:

const element = <h1>Hello, world</h1>;

Unlike browser DOM elements, React elements are plain objects, and are cheap to create. React DOM takes care of updating the DOM to match the React elements.

Note:One might confuse elements with a more widely known concept of "components". We will introduce components in the next section. Elements are what components are "made of", and we encourage you to read this section before jumping ahead.

Let's say there is a <div> somewhere in your HTML file:

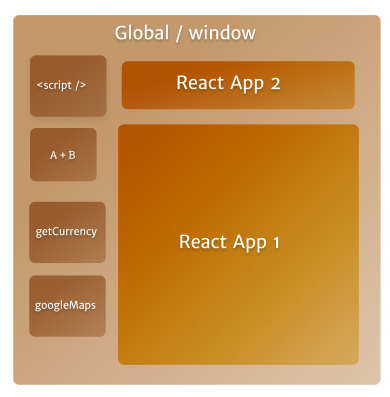

<div id="root"></div>

We call this a "root" DOM node because everything inside it will be managed by React DOM.

Applications built with just React usually have a single root DOM node. If you are integrating React into an existing app, you may have as many isolated root DOM nodes as you like.

To render a React element into a root DOM node, pass both to [ReactDOM.render()](<https://reactjs.org/docs/react-dom.html#render>):

const element = <h1>Hello, world</h1>;

ReactDOM.render(element, document.getElementById('root'));

https://codepen.io/bgoonz/pen/mdwyWeb?editors=0010

It displays "Hello, world" on the page.

React elements are immutable. Once you create an element, you can't change its children or attributes. An element is like a single frame in a movie: it represents the UI at a certain point in time.

With our knowledge so far, the only way to update the UI is to create a new element, and pass it to [ReactDOM.render()](<https://reactjs.org/docs/react-dom.html#render>).

Consider this ticking clock example:

function tick() {

const element = (

<div> <h1>Hello, world!</h1> <h2>It is {new Date().toLocaleTimeString()}.</h2> </div>);

ReactDOM.render(element, document.getElementById('root'));}

setInterval(tick, 1000);

https://codepen.io/bgoonz/pen/eYRmvNy?editors=0010

It calls [ReactDOM.render()](<https://reactjs.org/docs/react-dom.html#render>) every second from a [setInterval()](<https://developer.mozilla.org/en-US/docs/Web/API/WindowTimers/setInterval>) callback.

Note:In practice, most React apps only call ReactDOM.render() once. In the next sections we will learn how such code gets encapsulated into stateful components.We recommend that you don't skip topics because they build on each other.

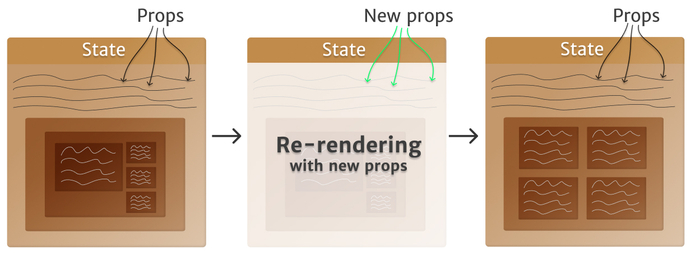

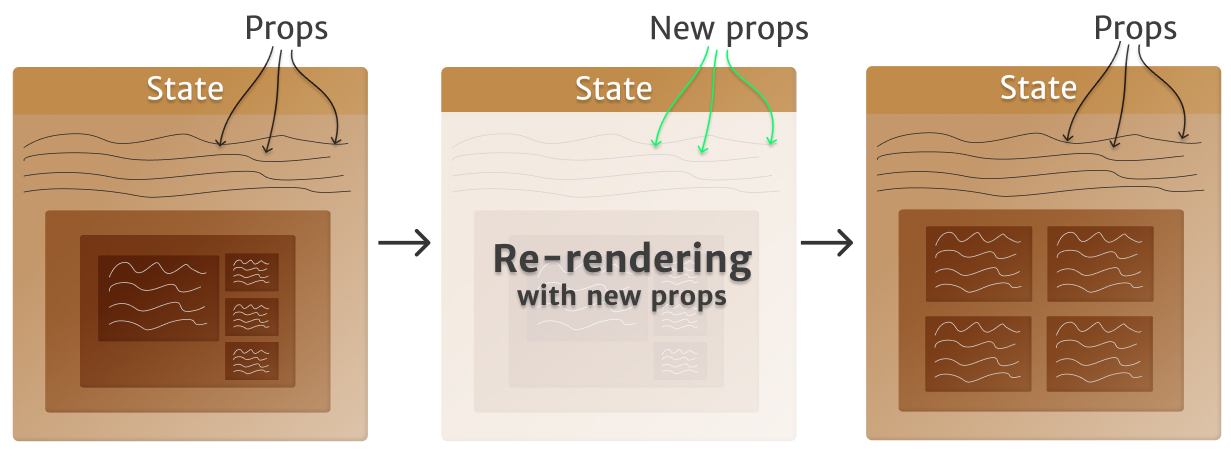

React DOM compares the element and its children to the previous one, and only applies the DOM updates necessary to bring the DOM to the desired state.

You can verify by inspecting the last example with the browser tools:

Even though we create an element describing the whole UI tree on every tick, only the text node whose contents have changed gets updated by React DOM.

In our experience, thinking about how the UI should look at any given moment, rather than how to change it over time, eliminates a whole class of bugs.

Components let you split the UI into independent, reusable pieces, and think about each piece in isolation. This page provides an introduction to the idea of components. You can find a detailed component API reference here.

Conceptually, components are like JavaScript functions. They accept arbitrary inputs (called "props") and return React elements describing what should appear on the screen.

The simplest way to define a component is to write a JavaScript function:

function Welcome(props) {

return <h1>Hello, {props.name}</h1>;

}

This function is a valid React component because it accepts a single "props" (which stands for properties) object argument with data and returns a React element. We call such components "function components" because they are literally JavaScript functions.

You can also use an ES6 class to define a component:

class Welcome extends React.Component {

render() {

return <h1>Hello, {this.props.name}</h1>;

}

}

The above two components are equivalent from React's point of view.

Function and Class components both have some additional features that we will discuss in the next sections.

Previously, we only encountered React elements that represent DOM tags:

const element = <div />;

However, elements can also represent user-defined components:

const element = <Welcome name="Sara" />;

When React sees an element representing a user-defined component, it passes JSX attributes and children to this component as a single object. We call this object "props".

For example, this code renders "Hello, Sara" on the page:

function Welcome(props) { return <h1>Hello, {props.name}</h1>;

}

const element = <Welcome name="Sara" />;ReactDOM.render(

element,

document.getElementById('root')

);

https://codepen.io/bgoonz/pen/QWgwpjd?editors=0010

Let's recap what happens in this example:

- We call

ReactDOM.render()with the<Welcome name="Sara" />element. - React calls the

Welcomecomponent with{name: 'Sara'}as the props. - Our

Welcomecomponent returns a<h1>Hello, Sara</h1>element as the result. - React DOM efficiently updates the DOM to match

<h1>Hello, Sara</h1>.

Note: Always start component names with a capital letter.React treats components starting with lowercase letters as DOM tags. For example,

represents an HTML div tag, but represents a component and requires Welcome to be in scope.To learn more about the reasoning behind this convention, please read JSX In Depth.

Components can refer to other components in their output. This lets us use the same component abstraction for any level of detail. A button, a form, a dialog, a screen: in React apps, all those are commonly expressed as components.

For example, we can create an App component that renders Welcome many times:

function Welcome(props) {

return <h1>Hello, {props.name}</h1>;

}

function App() {

return (

<div> <Welcome name="Sara" /> <Welcome name="Cahal" /> <Welcome name="Edite" /> </div>);

}

ReactDOM.render(

<App />,

document.getElementById('root')

);

https://codepen.io/bgoonz/pen/LYLEWNq?editors=0010

Typically, new React apps have a single App component at the very top. However, if you integrate React into an existing app, you might start bottom-up with a small component like Button and gradually work your way to the top of the view hierarchy.

Don't be afraid to split components into smaller components.

For example, consider this Comment component:

function Comment(props) {

return (

<div className="Comment">

<div className="UserInfo">

<img className="Avatar"src={props.author.avatarUrl}alt={props.author.name}/>

<div className="UserInfo-name">

{props.author.name}

</div>

</div>

<div className="Comment-text">

{props.text}

</div>

<div className="Comment-date">

{formatDate(props.date)}

</div>

</div>);

}

https://codepen.io/bgoonz/pen/PojwpzP?editors=0010

It accepts author (an object), text (a string), and date (a date) as props, and describes a comment on a social media website.

This component can be tricky to change because of all the nesting, and it is also hard to reuse individual parts of it. Let's extract a few components from it.

First, we will extract Avatar:

function Avatar(props) {

return (

<img className="Avatar" src={props.user.avatarUrl} alt={props.user.name} /> );

}

The Avatar doesn't need to know that it is being rendered inside a Comment. This is why we have given its prop a more generic name: user rather than author.

We recommend naming props from the component's own point of view rather than the context in which it is being used.

We can now simplify Comment a tiny bit:

function Comment(props) {

return (

<div className="Comment"> <div className="UserInfo"> <Avatar user={props.author} /> <div className="UserInfo-name"> {props.author.name}

</div> </div> <div className="Comment-text"> {props.text}

</div> <div className="Comment-date"> {formatDate(props.date)}

</div> </div>);

}

Next, we will extract a UserInfo component that renders an Avatar next to the user's name:

function UserInfo(props) { return ( <div className="UserInfo"> <Avatar user={props.user} /> <div className="UserInfo-name"> {props.user.name} </div> </div> ); }

This lets us simplify Comment even further:

function Comment(props) {

return (

<div className="Comment"> <UserInfo user={props.author} /> <div className="Comment-text"> {props.text}

</div> <div className="Comment-date"> {formatDate(props.date)}

</div> </div>);

}

https://codepen.io/bgoonz/pen/eYRmvzV?editors=0010

Extracting components might seem like grunt work at first, but having a palette of reusable components pays off in larger apps. A good rule of thumb is that if a part of your UI is used several times (Button, Panel, Avatar), or is complex enough on its own (App, FeedStory, Comment), it is a good candidate to be extracted to a separate component.

Whether you declare a component as a function or a class, it must never modify its own props. Consider this sum function:

function sum(a, b) {

return a + b;

}

Such functions are called "pure" because they do not attempt to change their inputs, and always return the same result for the same inputs.

In contrast, this function is impure because it changes its own input:

function withdraw(account, amount) {

account.total -= amount;

}

React is pretty flexible but it has a single strict rule:

All React components must act like pure functions with respect to their props.

Of course, application UIs are dynamic and change over time. In the next section, we will introduce a new concept of "state". State allows React components to change their output over time in response to user actions, network responses, and anything else, without violating this rule.

This page introduces the concept of state and lifecycle in a React component. You can find a detailed component API reference here.

Consider the ticking clock example from one of the previous sections. In Rendering Elements, we have only learned one way to update the UI. We call ReactDOM.render() to change the rendered output:

function tick() {

const element = (

<div> <h1>Hello, world!</h1> <h2>It is {new Date().toLocaleTimeString()}.</h2> </div>);

ReactDOM.render( element, document.getElementById('root') );}

setInterval(tick, 1000);

In this section, we will learn how to make the Clock component truly reusable and encapsulated. It will set up its own timer and update itself every second.

We can start by encapsulating how the clock looks:

function Clock(props) {

return (

<div> <h1>Hello, world!</h1> <h2>It is {props.date.toLocaleTimeString()}.</h2> </div> );

}

function tick() {

ReactDOM.render(

<Clock date={new Date()} />, document.getElementById('root')

);

}

setInterval(tick, 1000);

https://codepen.io/bgoonz/pen/powvegw?editors=0010

However, it misses a crucial requirement: the fact that the Clock sets up a timer and updates the UI every second should be an implementation detail of the Clock.

Ideally we want to write this once and have the Clock update itself:

ReactDOM.render(

<Clock />, document.getElementById('root')

);

To implement this, we need to add "state" to the Clock component.

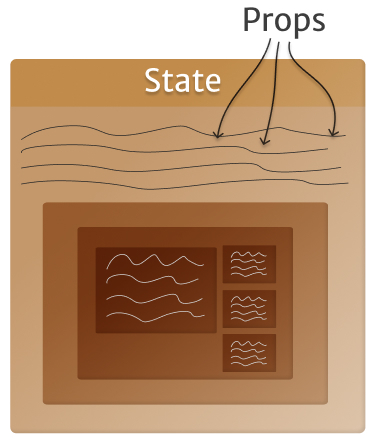

State is similar to props, but it is private and fully controlled by the component.

You can convert a function component like Clock to a class in five steps:

- Create an ES6 class, with the same name, that extends

React.Component. - Add a single empty method to it called

render(). - Move the body of the function into the

render()method. - Replace

propswiththis.propsin therender()body. - Delete the remaining empty function declaration.

class Clock extends React.Component {

render() {

return (

<div>

<h1>Hello, world!</h1>

<h2>It is {this.props.date.toLocaleTimeString()}.</h2>

</div>);

}

}

https://codepen.io/bgoonz/pen/eYRmvJV?editors=0010

Clock is now defined as a class rather than a function.

The render method will be called each time an update happens, but as long as we render <Clock /> into the same DOM node, only a single instance of the Clock class will be used. This lets us use additional features such as local state and lifecycle methods.

We will move the date from props to state in three steps:

- Replace

this.props.datewiththis.state.datein therender()method:

class Clock extends React.Component {

render() {

return (

<div> <h1>Hello, world!</h1> <h2>It is {this.state.date.toLocaleTimeString()}.</h2> </div>);

}

}

- Add a class constructor that assigns the initial

this.state:

class Clock extends React.Component {

constructor(props) {

super(props);

this.state = {date: new Date()}; }

render() {

return (

<div> <h1>Hello, world!</h1> <h2>It is {this.state.date.toLocaleTimeString()}.</h2> </div>);

}

}

Note how we pass props to the base constructor:

constructor(props) {

super(props); this.state = {date: new Date()};

}

Class components should always call the base constructor with props.

- Remove the

dateprop from the<Clock />element:

ReactDOM.render(

<Clock />, document.getElementById('root')

);

We will later add the timer code back to the component itself.

The result looks like this:

class Clock extends React.Component {

constructor(props) { super(props); this.state = {date: new Date()}; }render() {

return (

<div> <h1>Hello, world!</h1> <h2>It is {this.state.date.toLocaleTimeString()}.</h2> </div>);

}

}

ReactDOM.render(

<Clock />, document.getElementById('root')

);

https://codepen.io/bgoonz/pen/oNwgZbV?editors=0010

Next, we'll make the Clock set up its own timer and update itself every second.

In applications with many components, it's very important to free up resources taken by the components when they are destroyed.

We want to set up a timer whenever the Clock is rendered to the DOM for the first time. This is called "mounting" in React.

We also want to clear that timer whenever the DOM produced by the Clock is removed. This is called "unmounting" in React.

We can declare special methods on the component class to run some code when a component mounts and unmounts:

class Clock extends React.Component {

constructor(props) {

super(props);

this.state = {date: new Date()};

}

componentDidMount() { } componentWillUnmount() { }render() {

return (

<div> <h1>Hello, world!</h1> <h2>It is {this.state.date.toLocaleTimeString()}.</h2> </div>);

}

}

These methods are called "lifecycle methods".

The componentDidMount() method runs after the component output has been rendered to the DOM. This is a good place to set up a timer:

componentDidMount() {

this.timerID = setInterval( () => this.tick(), 1000 ); }

Note how we save the timer ID right on this (this.timerID).

While this.props is set up by React itself and this.state has a special meaning, you are free to add additional fields to the class manually if you need to store something that doesn't participate in the data flow (like a timer ID).

We will tear down the timer in the componentWillUnmount() lifecycle method:

componentWillUnmount() {

clearInterval(this.timerID); }

Finally, we will implement a method called tick() that the Clock component will run every second.

It will use this.setState() to schedule updates to the component local state:

class Clock extends React.Component {

constructor(props) {

super(props);

this.state = {date: new Date()};

}

componentDidMount() {

this.timerID = setInterval(

() => this.tick(),

1000

);

}

componentWillUnmount() {

clearInterval(this.timerID);

}

tick() { this.setState({ date: new Date() }); }render() {

return (

<div> <h1>Hello, world!</h1> <h2>It is {this.state.date.toLocaleTimeString()}.</h2> </div>);

}

}

ReactDOM.render(

<Clock />,

document.getElementById('root')

);

Now the clock ticks every second.

Let's quickly recap what's going on and the order in which the methods are called:

- When

<Clock />is passed toReactDOM.render(), React calls the constructor of theClockcomponent. SinceClockneeds to display the current time, it initializesthis.statewith an object including the current time. We will later update this state. - React then calls the

Clockcomponent'srender()method. This is how React learns what should be displayed on the screen. React then updates the DOM to match theClock's render output. - When the

Clockoutput is inserted in the DOM, React calls thecomponentDidMount()lifecycle method. Inside it, theClockcomponent asks the browser to set up a timer to call the component'stick()method once a second. - Every second the browser calls the

tick()method. Inside it, theClockcomponent schedules a UI update by callingsetState()with an object containing the current time. Thanks to thesetState()call, React knows the state has changed, and calls therender()method again to learn what should be on the screen. This time,this.state.datein therender()method will be different, and so the render output will include the updated time. React updates the DOM accordingly. - If the

Clockcomponent is ever removed from the DOM, React calls thecomponentWillUnmount()lifecycle method so the timer is stopped.

There are three things you should know about setState().

For example, this will not re-render a component:

// Wrong

this.state.comment = 'Hello';

Instead, use setState():

// Correct

this.setState({comment: 'Hello'});

The only place where you can assign this.state is the constructor.

React may batch multiple setState() calls into a single update for performance.

Because this.props and this.state may be updated asynchronously, you should not rely on their values for calculating the next state.

For example, this code may fail to update the counter:

// Wrong

this.setState({

counter: this.state.counter + this.props.increment,

});

To fix it, use a second form of setState() that accepts a function rather than an object. That function will receive the previous state as the first argument, and the props at the time the update is applied as the second argument:

// Correct

this.setState((state, props) => ({

counter: state.counter + props.increment

}));

We used an arrow function above, but it also works with regular functions:

// Correct

this.setState(function(state, props) {

return {

counter: state.counter + props.increment

};

});

When you call setState(), React merges the object you provide into the current state.

For example, your state may contain several independent variables:

constructor(props) {

super(props);

this.state = {

posts: [], comments: [] };

}

Then you can update them independently with separate setState() calls:

componentDidMount() {

fetchPosts().then(response => {

this.setState({

posts: response.posts });

});

fetchComments().then(response => {

this.setState({

comments: response.comments });

});

}

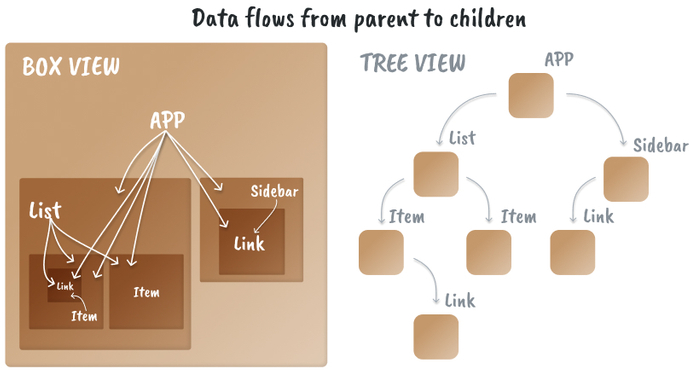

The merging is shallow, so this.setState({comments}) leaves this.state.posts intact, but completely replaces this.state.comments.

Neither parent nor child components can know if a certain component is stateful or stateless, and they shouldn't care whether it is defined as a function or a class.

This is why state is often called local or encapsulated. It is not accessible to any component other than the one that owns and sets it.

A component may choose to pass its state down as props to its child components:

<FormattedDate date={this.state.date} />

The FormattedDate component would receive the date in its props and wouldn't know whether it came from the Clock's state, from the Clock's props, or was typed by hand:

function FormattedDate(props) {

return <h2>It is {props.date.toLocaleTimeString()}.</h2>;

}

https://codepen.io/bgoonz/pen/GREgWEp?editors=0010

This is commonly called a "top-down" or "unidirectional" data flow. Any state is always owned by some specific component, and any data or UI derived from that state can only affect components "below" them in the tree.

If you imagine a component tree as a waterfall of props, each component's state is like an additional water source that joins it at an arbitrary point but also flows down.

To show that all components are truly isolated, we can create an App component that renders three <Clock>s:

function App() {

return (

<div> <Clock /> <Clock /> <Clock /> </div>);

}

ReactDOM.render(

<App />,

document.getElementById('root')

);

https://codepen.io/bgoonz/pen/YzQPZQK?editors=0010

Each Clock sets up its own timer and updates independently.

In React apps, whether a component is stateful or stateless is considered an implementation detail of the component that may change over time. You can use stateless components inside stateful components, and vice versa.

Handling events with React elements is very similar to handling events on DOM elements. There are some syntax differences:

- React events are named using camelCase, rather than lowercase.

- With JSX you pass a function as the event handler, rather than a string.

For example, the HTML:

<button onclick="activateLasers()">

Activate Lasers

</button>

is slightly different in React:

<button onClick={activateLasers}> Activate Lasers

</button>

Another difference is that you cannot return false to prevent default behavior in React. You must call preventDefault explicitly. For example, with plain HTML, to prevent the default form behavior of submitting, you can write:

<form onsubmit="console.log('You clicked submit.'); return false"><button type="submit">Submit</button></form>

In React, this could instead be:

function Form() {

function handleSubmit(e) {

e.preventDefault(); console.log('You clicked submit.');

}

return (

<form onSubmit={handleSubmit}> <button type="submit">Submit</button> </form>);

}

Here, e is a synthetic event. React defines these synthetic events according to the W3C spec, so you don't need to worry about cross-browser compatibility. React events do not work exactly the same as native events. See the [SyntheticEvent](<https://reactjs.org/docs/events.html>) reference guide to learn more.

When using React, you generally don't need to call addEventListener to add listeners to a DOM element after it is created. Instead, just provide a listener when the element is initially rendered.

When you define a component using an ES6 class, a common pattern is for an event handler to be a method on the class. For example, this Toggle component renders a button that lets the user toggle between "ON" and "OFF" states:

class Toggle extends React.Component {

constructor(props) {

super(props);

this.state = {isToggleOn: true};

// This binding is necessary to make `this` work in the callback this.handleClick = this.handleClick.bind(this); }

handleClick() { this.setState(prevState => ({ isToggleOn: !prevState.isToggleOn })); }render() {

return (

<button onClick={this.handleClick}> {this.state.isToggleOn ? 'ON' : 'OFF'}

</button>);

}

}

ReactDOM.render(

<Toggle />,

document.getElementById('root')

);

You have to be careful about the meaning of this in JSX callbacks. In JavaScript, class methods are not bound by default. If you forget to bind this.handleClick and pass it to onClick, this will be undefined when the function is actually called.

This is not React-specific behavior; it is a part of how functions work in JavaScript. Generally, if you refer to a method without () after it, such as onClick={this.handleClick}, you should bind that method.

If calling bind annoys you, there are two ways you can get around this. If you are using the experimental public class fields syntax, you can use class fields to correctly bind callbacks:

class LoggingButton extends React.Component {

// This syntax ensures `this` is bound within handleClick. // Warning: this is *experimental* syntax. handleClick = () => { console.log('this is:', this); }render() {

return (

<button onClick={this.handleClick}> Click me

</button>);

}

}

This syntax is enabled by default in Create React App.

If you aren't using class fields syntax, you can use an arrow function in the callback:

class LoggingButton extends React.Component {

handleClick() {

console.log('this is:', this);

}

render() {

// This syntax ensures `this` is bound within handleClick return ( <button onClick={() => this.handleClick()}> Click me

</button>);

}

}

The problem with this syntax is that a different callback is created each time the LoggingButton renders. In most cases, this is fine. However, if this callback is passed as a prop to lower components, those components might do an extra re-rendering. We generally recommend binding in the constructor or using the class fields syntax, to avoid this sort of performance problem.

Inside a loop, it is common to want to pass an extra parameter to an event handler. For example, if id is the row ID, either of the following would work:

<button onClick={(e) => this.deleteRow(id, e)}>Delete Row</button><button onClick={this.deleteRow.bind(this, id)}>Delete Row</button>

The above two lines are equivalent, and use arrow functions and [Function.prototype.bind](<https://developer.mozilla.org/en-US/docs/Web/JavaScript/Reference/Global_objects/Function/bind>) respectively.

In both cases, the e argument representing the React event will be passed as a second argument after the ID. With an arrow function, we have to pass it explicitly, but with bind any further arguments are automatically forwarded.

In React, you can create distinct components that encapsulate behavior you need. Then, you can render only some of them, depending on the state of your application.

Conditional rendering in React works the same way conditions work in JavaScript. Use JavaScript operators like [if](<https://developer.mozilla.org/en-US/docs/Web/JavaScript/Reference/Statements/if...else>) or the conditional operator to create elements representing the current state, and let React update the UI to match them.

Consider these two components:

function UserGreeting(props) {

return <h1>Welcome back!</h1>;

}

function GuestGreeting(props) {

return <h1>Please sign up.</h1>;

}

We'll create a Greeting component that displays either of these components depending on whether a user is logged in:

function Greeting(props) {

const isLoggedIn = props.isLoggedIn;

if (isLoggedIn) { return <UserGreeting />; } return <GuestGreeting />;}

ReactDOM.render(

// Try changing to isLoggedIn={true}:

<Greeting isLoggedIn={false} />, document.getElementById('root'));

https://codepen.io/bgoonz/pen/mdwyWmJ?editors=0011

This example renders a different greeting depending on the value of isLoggedIn prop.

You can use variables to store elements. This can help you conditionally render a part of the component while the rest of the output doesn't change.

Consider these two new components representing Logout and Login buttons:

function LoginButton(props) {

return (

<button onClick={props.onClick}>

Login

</button>);

}

function LogoutButton(props) {

return (

<button onClick={props.onClick}>

Logout

</button>);

}

In the example below, we will create a stateful component called LoginControl.

It will render either <LoginButton /> or <LogoutButton /> depending on its current state. It will also render a <Greeting /> from the previous example:

class LoginControl extends React.Component {

constructor(props) {

super(props);

this.handleLoginClick = this.handleLoginClick.bind(this);

this.handleLogoutClick = this.handleLogoutClick.bind(this);

this.state = {isLoggedIn: false};

}

handleLoginClick() {

this.setState({isLoggedIn: true});

}

handleLogoutClick() {

this.setState({isLoggedIn: false});

}

render() {

const isLoggedIn = this.state.isLoggedIn;

let button;

if (isLoggedIn) { button = <LogoutButton onClick={this.handleLogoutClick} />; } else { button = <LoginButton onClick={this.handleLoginClick} />; }return (

<div> <Greeting isLoggedIn={isLoggedIn} /> {button} </div>);

}

}

ReactDOM.render(

<LoginControl />,

document.getElementById('root')

);

While declaring a variable and using an if statement is a fine way to conditionally render a component, sometimes you might want to use a shorter syntax. There are a few ways to inline conditions in JSX, explained below.

You may embed expressions in JSX by wrapping them in curly braces. This includes the JavaScript logical && operator. It can be handy for conditionally including an element:

function Mailbox(props) {

const unreadMessages = props.unreadMessages;

return (

<div> <h1>Hello!</h1> {unreadMessages.length > 0 && <h2> You have {unreadMessages.length} unread messages. </h2> } </div>);

}

const messages = ['React', 'Re: React', 'Re:Re: React'];

ReactDOM.render(

<Mailbox unreadMessages={messages} />,

document.getElementById('root')

);

https://codepen.io/bgoonz/pen/VwWYppo?editors=0010

It works because in JavaScript, true && expression always evaluates to expression, and false && expression always evaluates to false.

Therefore, if the condition is true, the element right after && will appear in the output. If it is false, React will ignore and skip it.

Note that returning a falsy expression will still cause the element after && to be skipped but will return the falsy expression. In the example below, <div>0</div> will be returned by the render method.

render() {

const count = 0; return (

<div> { count && <h1>Messages: {count}</h1>} </div>);

}

Another method for conditionally rendering elements inline is to use the JavaScript conditional operator [condition ? true : false](<https://developer.mozilla.org/en/docs/Web/JavaScript/Reference/Operators/Conditional_Operator>).

In the example below, we use it to conditionally render a small block of text.

render() {

const isLoggedIn = this.state.isLoggedIn;

return (

<div> The user is <b>{isLoggedIn ? 'currently' : 'not'}</b> logged in. </div>);

}

It can also be used for larger expressions although it is less obvious what's going on:

render() {

const isLoggedIn = this.state.isLoggedIn;

return (

<div> {isLoggedIn ? <LogoutButton onClick={this.handleLogoutClick} /> : <LoginButton onClick={this.handleLoginClick} /> }

</div> );

}

Just like in JavaScript, it is up to you to choose an appropriate style based on what you and your team consider more readable. Also remember that whenever conditions become too complex, it might be a good time to extract a component.

In rare cases you might want a component to hide itself even though it was rendered by another component. To do this return null instead of its render output.

In the example below, the <WarningBanner /> is rendered depending on the value of the prop called warn. If the value of the prop is false, then the component does not render:

function WarningBanner(props) {

if (!props.warn) { return null; }return (

<div className="warning"> Warning!

</div>);

}

class Page extends React.Component {

constructor(props) {

super(props);

this.state = {showWarning: true};

this.handleToggleClick = this.handleToggleClick.bind(this);

}

handleToggleClick() {

this.setState(state => ({

showWarning: !state.showWarning

}));

}

render() {

return (

<div> <WarningBanner warn={this.state.showWarning} /> <button onClick={this.handleToggleClick}> {this.state.showWarning ? 'Hide' : 'Show'}

</button> </div>);

}

}

ReactDOM.render(

<Page />,

document.getElementById('root')

);

Returning null from a component's render method does not affect the firing of the component's lifecycle methods. For instance componentDidUpdate will still be called.

Given the code below, we use the [map()](<https://developer.mozilla.org/en-US/docs/Web/JavaScript/Reference/Global_Objects/Array/map>) function to take an array of numbers and double their values. We assign the new array returned by map() to the variable doubled and log it:

const numbers = [1, 2, 3, 4, 5];

const doubled = numbers.map((number) => number * 2);console.log(doubled);

This code logs [2, 4, 6, 8, 10] to the console.

In React, transforming arrays into lists of elements is nearly identical.

You can build collections of elements and include them in JSX using curly braces {}.

Below, we loop through the numbers array using the JavaScript [map()](<https://developer.mozilla.org/en-US/docs/Web/JavaScript/Reference/Global_Objects/Array/map>) function. We return a <li> element for each item. Finally, we assign the resulting array of elements to listItems:

const numbers = [1, 2, 3, 4, 5];

const listItems = numbers.map((number) => <li>{number}</li>);

We include the entire listItems array inside a <ul> element, and render it to the DOM:

ReactDOM.render(

<ul>{listItems}</ul>, document.getElementById('root')

);

https://codepen.io/bgoonz/pen/eYRmvvr?editors=0011

This code displays a bullet list of numbers between 1 and 5.

Usually you would render lists inside a component.

We can refactor the previous example into a component that accepts an array of numbers and outputs a list of elements.

function NumberList(props) {

const numbers = props.numbers;

const listItems = numbers.map((number) => <li>{number}</li> ); return (

<ul>{listItems}</ul> );

}

const numbers = [1, 2, 3, 4, 5];

ReactDOM.render(

<NumberList numbers={numbers} />, document.getElementById('root')

);

When you run this code, you'll be given a warning that a key should be provided for list items. A "key" is a special string attribute you need to include when creating lists of elements. We'll discuss why it's important in the next section.

Let's assign a key to our list items inside numbers.map() and fix the missing key issue.

function NumberList(props) {

const numbers = props.numbers;

const listItems = numbers.map((number) =>

<li key={number.toString()}> {number}

</li>);

return (

<ul>{listItems}</ul>);

}

const numbers = [1, 2, 3, 4, 5];

ReactDOM.render(

<NumberList numbers={numbers} />,

document.getElementById('root')

);

https://codepen.io/bgoonz/pen/yLXyMMP?editors=0011

Keys help React identify which items have changed, are added, or are removed. Keys should be given to the elements inside the array to give the elements a stable identity:

const numbers = [1, 2, 3, 4, 5];

const listItems = numbers.map((number) =>

<li key={number.toString()}> {number}

</li>);

The best way to pick a key is to use a string that uniquely identifies a list item among its siblings. Most often you would use IDs from your data as keys:

const todoItems = todos.map((todo) =>

<li key={todo.id}> {todo.text}

</li>);

When you don't have stable IDs for rendered items, you may use the item index as a key as a last resort:

const todoItems = todos.map((todo, index) =>

// Only do this if items have no stable IDs <li key={index}> {todo.text}

</li>);

We don't recommend using indexes for keys if the order of items may change. This can negatively impact performance and may cause issues with component state. Check out Robin Pokorny's article for an in-depth explanation on the negative impacts of using an index as a key. If you choose not to assign an explicit key to list items then React will default to using indexes as keys.

Here is an in-depth explanation about why keys are necessary if you're interested in learning more.

Keys only make sense in the context of the surrounding array.