-

Notifications

You must be signed in to change notification settings - Fork 24

Commit

This commit does not belong to any branch on this repository, and may belong to a fork outside of the repository.

- Loading branch information

1 parent

ae12a55

commit e505e91

Showing

1 changed file

with

271 additions

and

0 deletions.

There are no files selected for viewing

This file contains bidirectional Unicode text that may be interpreted or compiled differently than what appears below. To review, open the file in an editor that reveals hidden Unicode characters.

Learn more about bidirectional Unicode characters

| Original file line number | Diff line number | Diff line change |

|---|---|---|

| @@ -0,0 +1,271 @@ | ||

| --- | ||

| layout: post | ||

| title: "Day 21: Memory Segmentation" | ||

| permalink: /src/day-21-memory-segmentation.html | ||

| --- | ||

|

|

||

| # Day 21: Memory Segmentation | ||

|

|

||

| ## Table of Contents | ||

| * [Introduction](#introduction) | ||

| * [Segmentation Fundamentals](#segmentation-fundamentals) | ||

| * [Segment Table Architecture](#segment-table-architecture) | ||

| * [Address Translation in Segmentation](#address-translation-in-segmentation) | ||

| * [Implementation in C](#implementation-details) | ||

| * [Protection and Sharing](#protection-and-sharing) | ||

| * [Segmentation vs Paging](#segmentation-vs-paging) | ||

| * [Real-world Applications](#real-world-applications) | ||

| * [Performance Considerations](#performance-considerations) | ||

| * [Conclusion](#conclusion) | ||

| * [References and Further Reading](#references-and-further-reading) | ||

|

|

||

| ## 1. Introduction | ||

| Segmentation is a memory management technique that organizes memory based on the logical structure of a program. Unlike paging, which divides memory into fixed-size pages, segmentation divides a program into logical units called segments, such as code, data, stack, and heap. This allows for a more natural representation of the program's structure and facilitates features like protection and sharing. | ||

|

|

||

| Segmentation provides a programmer-friendly view of memory, aligning with how programs are typically organized. It also offers greater flexibility in terms of protection and sharing, allowing different access permissions for different segments and enabling efficient sharing of code or data segments between processes. | ||

|

|

||

| ## 2. Segmentation Fundamentals | ||

| Key concepts in segmentation include the logical address structure, segment properties, and memory organization. Understanding these concepts is essential for comprehending how segmentation works and its implications for memory management. | ||

|

|

||

| Segmentation uses a logical address composed of a segment number and an offset. The segment number identifies the segment, while the offset specifies the location within the segment. Each segment has properties like a base address, limit, and protection bits, which control its location, size, and access permissions in physical memory. | ||

|

|

||

| * **Logical Address Structure:** `<segment-number, offset>` - The segment number identifies the segment, and the offset indicates the location within that segment. | ||

| * **Segment Properties:** | ||

| * **Base Address:** Starting physical address of the segment. | ||

| * **Limit:** Length of the segment. | ||

| * **Protection Bits:** Access permissions (read, write, execute). | ||

| * **Valid Bit:** Indicates if the segment is currently loaded in memory. | ||

| * **Memory Organization:** Segmentation allows for variable-sized segments and non-contiguous allocation, supporting dynamic growth and a more natural mapping of program structure. | ||

|

|

||

| ## 3. Segment Table Architecture | ||

| The segment table is a crucial data structure in segmentation. It stores information about each segment, including its base address, limit, and protection bits. The segment table is used for address translation and access control. | ||

|

|

||

| [](https://mermaid.live/edit#pako:eNp1UtFOgzAU_ZXmvsoWJjKgD0uMJsaHJWZTH8xe7ujdIEI722LEZf9ut4IuYbYJgXvOuefc0j3kShBwMPTRkMzpvsStxnolmVs71LbMyx1Ky560ysmYIbCkbU3SPuO6oiE6n79cKFKtdOvr_tl1H81m5-04WxxjGctQCO1wZjVKU6EtlfTCc7pTOzvO7grK35nxCFurRoouN1aWvWJVih715eNyyoH7Azk5Gurt_9iXbBdkGy294IqpzcbQoL-fnLPb_Dgu2xWtKXOshgaeOHKS7mh--wu06HlUOadH-fn_QOfyLjLbYFN1NJICAqhJ11gKdwn2x_IKbEE1rYC7V0GeDit5cFRsrFq2MgdudUMBaNVsC-AbdEkCaHYuW3-Deor74W9KnX8C38MX8CweR2EUJmE4TaM4i9IAWuA36ThLJlGaJUkYh0k6OQTwfdKH4yw87XSaRddRnEwOPz-i4go) | ||

|

|

||

| Each entry in the segment table corresponds to a segment and contains information necessary for address translation and access control. This information includes the segment's base address in physical memory, its limit, and protection bits that determine access permissions. | ||

|

|

||

| ```c | ||

| typedef struct { | ||

| unsigned int base_address; // Base address of segment | ||

| unsigned int limit; // Length of segment | ||

| unsigned int protection_bits; // Access rights | ||

| unsigned char valid; // Present/absent bit | ||

| } SegmentTableEntry; | ||

|

|

||

| typedef struct { | ||

| SegmentTableEntry* entries; | ||

| unsigned int size; // Number of segments | ||

| } SegmentTable; | ||

| ``` | ||

|

|

||

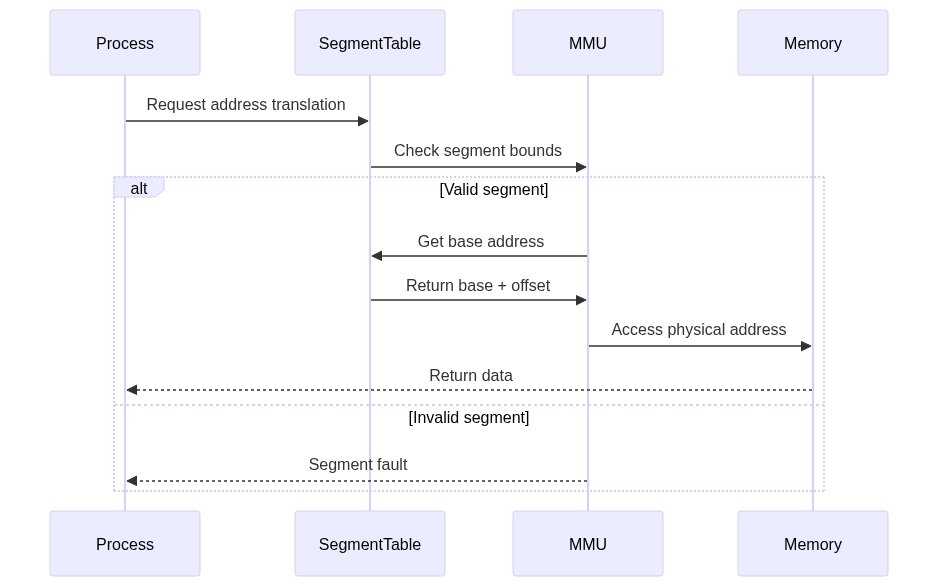

| ## 4. Address Translation in Segmentation | ||

| Address translation in segmentation involves mapping a logical address to a physical address. This is achieved using the segment table. The segment number in the logical address is used to index into the segment table, retrieving the base address of the segment. The offset is then added to the base address to obtain the physical address. Bounds checks are performed to ensure that the offset is within the segment's limit. | ||

|

|

||

| ## 5. Implementation in C | ||

|

|

||

| ```c | ||

| #include <stdio.h> | ||

| #include <stdlib.h> | ||

| #include <string.h> | ||

|

|

||

| #define MAX_SEGMENTS 256 | ||

| #define MAX_MEMORY_SIZE 65536 | ||

|

|

||

| #define READ_PERMISSION 4 | ||

| #define WRITE_PERMISSION 2 | ||

| #define EXEC_PERMISSION 1 | ||

|

|

||

| typedef struct { | ||

| unsigned int base_address; | ||

| unsigned int limit; | ||

| unsigned int protection_bits; | ||

| unsigned char valid; | ||

| } SegmentTableEntry; | ||

|

|

||

| typedef struct { | ||

| SegmentTableEntry entries[MAX_SEGMENTS]; | ||

| unsigned int size; | ||

| } SegmentTable; | ||

|

|

||

| typedef struct { | ||

| char* memory; | ||

| unsigned int size; | ||

| } PhysicalMemory; | ||

|

|

||

| SegmentTable* createSegmentTable() { | ||

| SegmentTable* table = (SegmentTable*)malloc(sizeof(SegmentTable)); | ||

| table->size = 0; | ||

|

|

||

| for(int i = 0; i < MAX_SEGMENTS; i++) { | ||

| table->entries[i].base_address = 0; | ||

| table->entries[i].limit = 0; | ||

| table->entries[i].protection_bits = 0; | ||

| table->entries[i].valid = 0; | ||

| } | ||

|

|

||

| return table; | ||

| } | ||

|

|

||

| int createSegment(SegmentTable* table, unsigned int size, unsigned int protection) { | ||

| if(table->size >= MAX_SEGMENTS) { | ||

| printf("Error: Maximum segments reached\n"); | ||

| return -1; | ||

| } | ||

|

|

||

| int segment_number = table->size++; | ||

| table->entries[segment_number].base_address = 0; // Will be set during allocation | ||

| table->entries[segment_number].limit = size; | ||

| table->entries[segment_number].protection_bits = protection; | ||

| table->entries[segment_number].valid = 1; | ||

|

|

||

| return segment_number; | ||

| } | ||

|

|

||

| unsigned int translateAddress(SegmentTable* table, unsigned int segment, unsigned int offset) { | ||

| if(segment >= table->size) { | ||

| printf("Error: Invalid segment number\n"); | ||

| return -1; | ||

| } | ||

|

|

||

| SegmentTableEntry* entry = &table->entries[segment]; | ||

|

|

||

| if(!entry->valid) { | ||

| printf("Error: Segment not in memory\n"); | ||

| return -1; | ||

| } | ||

|

|

||

| if(offset >= entry->limit) { | ||

| printf("Error: Segment overflow\n"); | ||

| return -1; | ||

| } | ||

|

|

||

| return entry->base_address + offset; | ||

| } | ||

|

|

||

| int checkAccess(SegmentTable* table, unsigned int segment, unsigned int access_type) { | ||

| if(segment >= table->size) return 0; | ||

|

|

||

| SegmentTableEntry* entry = &table->entries[segment]; | ||

| return (entry->protection_bits & access_type) != 0; | ||

| } | ||

|

|

||

| PhysicalMemory* initializePhysicalMemory() { | ||

| PhysicalMemory* memory = (PhysicalMemory*)malloc(sizeof(PhysicalMemory)); | ||

| memory->size = MAX_MEMORY_SIZE; | ||

| memory->memory = (char*)malloc(MAX_MEMORY_SIZE); | ||

| return memory; | ||

| } | ||

|

|

||

| int allocateSegment(SegmentTable* table, PhysicalMemory* memory, int segment_number) { | ||

| if(segment_number >= table->size) return -1; | ||

|

|

||

| SegmentTableEntry* entry = &table->entries[segment_number]; | ||

| unsigned int size = entry->limit; | ||

|

|

||

| // Simple first-fit allocation | ||

| unsigned int current_address = 0; | ||

| while(current_address + size <= memory->size) { | ||

| int space_available = 1; | ||

| for(unsigned int i = 0; i < size; i++) { | ||

| if(memory->memory[current_address + i] != 0) { | ||

| space_available = 0; | ||

| break; | ||

| } | ||

| } | ||

|

|

||

| if(space_available) { | ||

| entry->base_address = current_address; | ||

| return current_address; | ||

| } | ||

|

|

||

| current_address++; | ||

| } | ||

|

|

||

| return -1; | ||

| } | ||

|

|

||

| int main() { | ||

| SegmentTable* table = createSegmentTable(); | ||

| PhysicalMemory* memory = initializePhysicalMemory(); | ||

|

|

||

| int code_segment = createSegment(table, 1024, READ_PERMISSION | EXEC_PERMISSION); | ||

| int data_segment = createSegment(table, 2048, READ_PERMISSION | WRITE_PERMISSION); | ||

| int stack_segment = createSegment(table, 4096, READ_PERMISSION | WRITE_PERMISSION); | ||

|

|

||

| printf("Code segment allocated at: %d\n", | ||

| allocateSegment(table, memory, code_segment)); | ||

| printf("Data segment allocated at: %d\n", | ||

| allocateSegment(table, memory, data_segment)); | ||

| printf("Stack segment allocated at: %d\n", | ||

| allocateSegment(table, memory, stack_segment)); | ||

|

|

||

| unsigned int logical_address = 100; | ||

| unsigned int physical_address = translateAddress(table, data_segment, logical_address); | ||

| printf("Logical address %d in segment %d translates to physical address %d\n", | ||

| logical_address, data_segment, physical_address); | ||

|

|

||

| printf("Can write to data segment: %s\n", | ||

| checkAccess(table, data_segment, WRITE_PERMISSION) ? "Yes" : "No"); | ||

| printf("Can execute data segment: %s\n", | ||

| checkAccess(table, data_segment, EXEC_PERMISSION) ? "Yes" : "No"); | ||

|

|

||

| free(table); | ||

| free(memory->memory); | ||

| free(memory); | ||

|

|

||

| return 0; | ||

| } | ||

| ``` | ||

| ## 6. Protection and Sharing | ||

| Segmentation provides mechanisms for memory protection and sharing between processes. Protection is achieved by associating access rights with each segment. Sharing is facilitated by allowing multiple processes to have entries in their segment tables that point to the same physical memory region. | ||

| Protection bits in the segment table entries control access permissions for each segment. This allows different segments to have different access rights (read, write, execute), ensuring memory protection and preventing unauthorized access. Sharing is implemented by allowing multiple processes to access the same segment with potentially different access permissions. | ||

| ```c | ||

| void shareSegment(SegmentTable* source, SegmentTable* target, | ||

| int segment_number, int protection) { | ||

| if(segment_number >= source->size) return; | ||

| SegmentTableEntry* source_entry = &source->entries[segment_number]; | ||

| int new_segment = target->size++; | ||

| target->entries[new_segment] = *source_entry; | ||

| target->entries[new_segment].protection_bits = protection; | ||

| } | ||

| ``` | ||

|

|

||

| ## 7. Segmentation vs Paging | ||

| Segmentation and paging are different memory management techniques. Segmentation divides memory based on logical units, while paging divides memory into fixed-size pages. Each approach has its own advantages and disadvantages. | ||

|

|

||

| ## 8. Real-world Applications | ||

| While segmentation is not as widely used as paging in modern operating systems, it is still employed in certain contexts, such as the Intel x86 architecture and for specific purposes like thread-local storage in Linux. | ||

|

|

||

| ```c | ||

| struct x86_segment_descriptor { | ||

| unsigned short limit_low; | ||

| unsigned short base_low; | ||

| unsigned char base_middle; | ||

| unsigned char access; | ||

| unsigned char granularity; | ||

| unsigned char base_high; | ||

| }; | ||

| ``` | ||

|

|

||

| ## 9. Performance Considerations | ||

|

|

||

| * **Memory Fragmentation:** Segmentation can lead to external fragmentation as variable-sized segments are allocated and deallocated. | ||

| * **Address Translation:** Address translation in segmentation is more complex than in paging. | ||

| * **Memory Utilization:** Segmentation can provide better memory utilization than paging, especially for programs with well-defined segments. | ||

|

|

||

| ## 10. Conclusion | ||

|

|

||

| Segmentation offers a logical view of memory, flexible protection mechanisms, and support for sharing and dynamic growth. However, it can suffer from external fragmentation and has a more complex memory management scheme compared to paging. | ||

|

|

||

| ## 11. References and Further Reading | ||

|

|

||

| * Intel® 64 and IA-32 Architectures Software Developer's Manual | ||

| * Operating Systems: Three Easy Pieces by Remzi H. Arpaci-Dusseau | ||

| * Computer Architecture: A Quantitative Approach by Hennessy & Patterson | ||

| * Modern Operating Systems by Andrew S. Tanenbaum | ||

| * Understanding the Linux Kernel by Daniel P. Bovet |