-

Notifications

You must be signed in to change notification settings - Fork 46

readfile guide

In this guide, walk through file processing in Node.js, from handling files and editing metadata to working with links and directories.

As a Node.js developer, there’s a good chance that at some point you’ve imported the fs module and written some code that’s interacted with the file system.

What you might not know is that the fs module is a fully-featured, standards-based, cross-platform module that exposes not one, but three APIs that cater to synchronous and asynchronous programming styles.

In this article, we will thoroughly explore the world of Node.js file processing in Windows and Linux systems, with a focus on the fs module’s promise-based API.

All examples in this article are intended to be run in a Linux environment, but many will work in Windows, too. Look for notes throughout the article highlighting examples that won’t work in Windows. Regarding macOS — in most cases, the fs module works the same way it would on Linux, but there are some macOS-specific behaviors that are not covered in this article. Refer to the official Node.js documentation for macOS nuances.

The full source code for all examples is available on my GitHub under briandesousa/node-file-process.

The fs module is a core module built into Node.js. It has been around since the beginning, all the way back to the original Node.js v0.x releases.

Since its earliest days, the fs module has been aligned with POSIX file system standards. This means the code you write is somewhat portable across multiple operating systems, though especially between different flavors of Unix and Linux.

Although Windows is not a POSIX-compliant operating system, most of the fs module’s functions will still work. However, there are functions that are not portable simply because certain file system capabilities do not exist or are implemented differently in Windows.

As we review the fs module’s functions, keep in mind that the following functions will return errors or will have unexpected results on Windows:

- Functions to modify file permissions and ownership:

chmod()chown()

- Functions to work with hard and soft links:

link()symlink()readlink()lutimes()lchmod()lchown()

- Some metadata is either not set or displays unexpected values when using

stat()andlstat()

Since Node v10, the fs module has included three different APIs: synchronous, callback, and promise. All three APIs expose the same set of file system operations.

This article will focus on the newer promise-based API. However, there may be circumstances where you want or need to use the synchronous or callback APIs. For that reason, let’s take a moment to compare all three APIs.

The synchronous API exposes a set of functions that block execution to perform file system operations. These functions tend to be the simplest to use when you’re just getting started.

On the other hand, they are thread-blocking, which is very contrary to the non-blocking I/O design of Node.js. Still, there are times where you must process a file synchronously.

Here is an example of using the synchronous API to read the contents of a file:

import * as fs from 'fs'; const data = fs.readFileSync(path); console.log(data);

The callback API allows you to interact with the file system in an asynchronous way. Each of the callback API functions accept a callback function that is invoked when the operation is completed. For example, we can call the readFile function with an arrow function that receives an error if there is a failure or receives the data if the file is read successfully:

import * as fs from 'fs'; fs.readFile(path, (err, data) => { if (err) { console.error(err); } else { console.log(`file read complete, data: ${data}`); } });

This is a non-blocking approach that is usually more suitable for Node.js applications, but it comes with its own challenges. Using callbacks in asynchronous programming often results in callback hell. If you’re not careful with how you structure your code, you may end up with a complex stack of nested callback functions that can be difficult to read and maintain.

If synchronous APIs should be avoided when possible, and callback APIs may not be ideal, that leaves us with the promise API:

import * as fsPromises from 'fs/promises'; async function usingPromiseAPI(path) { const promise = fsPromises.readFile(path); console.log('do something else'); return await promise; }

The first thing you might notice is the difference in this import statement compared to the previous examples: the promise API is available from the promises subpath. If you are importing all functions in the promise API, the convention is to import them as fsPromises. Synchronous and callback API functions are typically imported as fs.

If you want to keep example code compact, import statements will be omitted from subsequent examples. Standard import naming conventions will be used to differentiate between APIs: fs to access synchronous and callback functions, and fsPromises to access promise functions.

The promise API allows you to take advantage of JavaScript’s async/await syntactic sugar to write asynchronous code in a synchronous way. The readFile() function called on line 4 above returns a promise. The code that follows appears to be executed synchronously. Finally, the promise is returned from the function. The await operator is optional, but since we have included it, the function will wait for the file operation to complete before returning.

It’s time to take the promise API for a test drive. Get comfortable. There are quite a few functions to cover, including ones that create, read, and update files and file metadata.

The promise API provides two different approaches to working with files.

The first approach uses a top-level set of functions that accept file paths. These functions manage the lifecycle of file and directory resource handles internally. You don’t need to worry about calling a close() function when you are done with the file or directory.

The second approach uses a set of functions available on a FileHandle object. A FileHandle acts as a reference to a file or directory on the file system. Here is how you can obtain a FileHandle object:

async function openFile(path) { let fileHandle; try { fileHandle = await fsPromises.open(path, 'r'); console.log(`opened ${path}, file descriptor is ${fileHandle.fd}`); const data = fileHandle.read() } catch (err) { console.error(err.message); } finally { fileHandle?.close(); } }

On line 4 above, we use fsPromises.open() to create a FileHandle for a file. We pass the r flag to indicate that the file should be opened in read-only mode. Any operations that attempt to modify the file will fail. (You can also specify other flags.)

The file’s contents are read using the read() function, which is directly available from the file handle object. On line 10, we need to explicitly close the file handle to avoid potential memory leaks.

All of the functions available in the FileHandle class are also available as top-level functions. We’ll continue to explore top-level functions, but it is good to know that this approach is available as well.

Reading a file seems like such a simple task. However, there are several different options that can be specified depending on what you need to do with a file:

const data = await fsPromises.readFile(path); const noData = await fsPromises.readFile(path, { flag: 'w'}); const base64data = await fsPromises.readFile(path, { encoding: 'base64' }); const controller = new AbortController(); const { signal } = controller; const promise = fsPromises.readFile(path, { signal: signal }); console.log(`started reading file at ${path}`); controller.abort(); console.log('read operation aborted before it could be completed') await promise;

Example 1 is as simple as it gets, if all you want to do is get the contents of a file.

In example 2, we don’t know if the file exists, so we pass the w file system flag to create it first, if necessary.

Example 3 demonstrates how you change the format of the data returned.

Example 4 demonstrates how to interrupt a file read operation and abort it. This could be useful when reading files that are large or slow to read.

The copyFile function can make a copy of a file and give you some control over what happens if the destination file exists already:

await fsPromises.copyFile('source.txt', 'dest.txt'); await fsPromises.copyFile('source.txt', 'dest.txt', fs.constants.COPYFILE_EXCL);

Example 1 will overwrite dest.txt if it exists already. In example 2, we pass in the COPYFILE_EXCL flag to override the default behavior and fail if dest.txt exists already.

There are three ways to write to a file:

- Append to a file

- Write to a file

- Truncate a file

Each of these functions helps to implement different use cases.

await fsPromises.appendFile('data.txt', '67890'); await fsPromises.appendFile('data2.txt', '123'); await fsPromises.writeFile('data3.txt', '67890'); await fsPromises.writeFile('data4.txt', '12345'); await fsPromises.truncate('data5.txt', 5);

Examples 1 and 2 demonstrate how to use the appendFile function to append data to existing or new files. If a file doesn’t exist, appendFile will create it first.

Examples 3 and 4 demonstrate how to use the writeFile function to write to existing or new files. The writeFile function will also create a file if it doesn’t exist before writing to it. However, if the file already exists and contains data, the contents of the file is overwritten without warning.

Example 5 demonstrates how to use the truncate function to trim the contents of a file. The arguments that are passed to this function can be confusing at first. You might expect a truncate function to accept the number of characters to strip from the end of the file, but actually we need to specify the number of characters to retain. In the case above, you can see that we entered a value of 5 to the truncate function, which removed the last five characters from the string 1234567890.

The promise API provides a single, performant watch function that can watch a file for changes.

const abortController = new AbortController(); const { signal } = abortController; setTimeout(() => abortController.abort(), 3000); const watchEventAsyncIterator = fsPromises.watch(path, { signal }); setTimeout(() => { fs.writeFileSync(path, 'new data'); console.log(`modified ${path}`); }, 1000); for await (const event of watchEventAsyncIterator) { console.log(`'${event.eventType}' watch event was raised for ${event.filename}`); }

The watch function can watch a file for changes indefinitely. Each time a change is observed, a watch event is raised. The watch function returns an async iterable, which is essentially a way for the function to return an unbounded series of promises. On line 12, we take advantage of the for await … of syntactic sugar to wait for and iterate each watch event as it is received.

There is a good chance you don’t want to endlessly watch a file for changes. The watch can be aborted by using a special signal object that can be triggered as required. On lines 1 to 2, we create an instance of AbortController, which gives us access to an instance of AbortSignal that is ultimately passed to the watch function. In this example, we call the signal object’s abort() function after a fixed period of time (specified on line 3), but you can abort however and whenever you need to.

The watch function can also be used to watch the contents of a directory. It accepts an optional recursive option that determines whether all subdirectories and files are watched.

So far, we have focused on reading and modifying the contents of a file, but you may also need to read and update a file’s metadata. File metadata includes its size, type, permissions, and other file system properties.

The stat function is used to retrieve file metadata, or “statistics” like file size, permissions, and ownership.

const fileStats = await fsPromises.stat('file1.txt'); console.log(fileStats) console.log(`size of file1.txt is ${fileStats.size}`);

This example demonstrates the full list of metadata that can be retrieved for a file or directory.

Keep in mind that some of this metadata is OS-dependent. For example, the uid and gid properties represent the user and group owners — a concept that is applicable to Linux and macOS file systems, but not Windows file systems. Zeroes are returned for these two properties when running in this function on Windows.

Some file metadata can be manipulated. For example, the utimes function is used to update the access and modification timestamps on a file:

const newAccessTime = new Date(2020,0,1); const newModificationTime = new Date(2020,0,1); await fsPromises.utimes('test1.txt', newAccessTime, newModificationTime);

The realpath function is useful for resolving relative paths and symbolic links to full paths:

const realPath = await fsPromises.realpath('./test1.txt'); console.log(realPath); const symLinkRealPath = await fsPromises.realpath('./symlink1'); console.log(symLinkRealPath);

Please keep in mind as we continue in this section that file permission and ownership functions are applicable to Unix, Linux and macOS operating systems. These functions yield unexpected results on Windows.

If you are not sure whether your application has the necessary permissions to access or execute files on the file system, you can use the access function to test it:

try { await fsPromises.access('test1.txt'); console.log('test1.txt can be accessed'); } catch (err) { } try { await fsPromises.access('test2.txt', fs.constants.X_OK); } catch(err) { }

File permissions can be modified using the chmod function. For example, we can remove execute access from a file by passing a special mode string:

// remove all execute access from a file await fsPromises.chmod('test1.txt', '00666');

The 00666 mode string is a special five-digit number that is composed of multiple bit masks that describe file attributes including permissions. The last three digits are equivalent to the three-digit permission mode you might be used to passing to chmod on Linux. The fs module documentation provides a list of bit masks that can be used interpret this mode string.

File ownership can also be modified using the chown function:

// set user and group ownership on a file const root_uid= 0; const root_gid = 0; await fsPromises.chown('test1.txt', root_uid, root_gid);

In this example, we update the file so that it is owned by the root user and root group. The uid of the root user and gid of the root group are always 0 on Linux.

Tip: Link functions are applicable to Unix/Linux operating systems. These functions yield unexpected results on Windows.

The fs module provides a variety of functions you can use to work with hard and soft, or symbolic, links. Many of the file functions we’ve already seen have equivalent versions for working with links. In most cases, they operate identically, too.

Before we start creating links, let’s have a quick refresher on the two types of links we’ll be working with.

Hard and soft links are special types of files that point to other files on the file system. A soft link becomes invalid if the file it is linked to is deleted.

On the other hand, a hard link pointing to a file will still be valid and contain the file’s contents even if the original file is deleted. Hard links don’t point to a file, but rather a file’s underlying data. This data is referred to as the inode on Unix/Linux file systems.

We can easily create soft and hard links with the fs module. Use the symlink function to create soft links and the link function to create hard links.

const softLink = await fsPromises.symlink('file.txt', 'softLinkedFile.txt'); const hardLink = await fsPromises.link('file.txt', 'hardLinkedFile.txt');

What if you want to determine the underlying file that a link points to? This is where the readlink function comes in.

> console.log(await fsPromises.readlink('softLinkedFile.txt')); console.log(await fsPromises.readLink('hardLinkedFile.txt'));

The readlink function can read soft links, but not hard links. A hard link is indistinguishable from the original file it links to. In fact, all files are technically hard links. The readlink function essentially sees it as just another regular file and throws an EINVAL error.

The unlink function can remove both hard and soft links:

// delete a soft link await fsPromises.unlink('softLinkedFile.txt'); // delete a hard link / file await fsPromises.unlink('hardLinkedFile.txt');

The unlink function actually serves as a general purpose function that can also be used to delete regular files, since they are essentially the same as a hard link. Aside from the link and unlink functions, all other link functions are intended to be used with soft links.

You can modify a soft link’s metadata much like you would a normal file’s:

const linkStats = await fsPromises.lstat(path); const newAccessTime = new Date(2020,0,1); const newModifyTime = new Date(2020,0,1); await fsPromises.lutimes('softLinkedFile.txt', newAccessTime, newModifyTime); await fsPromises.lchmod('softLinkedFile.txt', '00666'); const root_uid= 0; const root_gid = 0; await fsPromises.lchown('softLinkedFile.txt', root_uid, root_gid);

Aside from each function being prefixed with an l, these functions operate identically to their equivalent file functions.

We can’t just stop at file processing. If you are working with files, it is inevitable that you will need to work with directories too. The fs module provides a variety of functions for creating, modifying, and deleting directories.

Much like the open function we saw earlier, the opendir function returns a handle to a directory in the form of a Dir object. The Dir object exposes several functions that can be used to operate on that directory:

let dir; try { dir = await fsPromises.opendir('sampleDir'); dirents = await dir.read(); } catch (err) { console.log(err); } finally { dir.close(); }

Be sure to call the close function to release the handle on the directory when you are done with it.

The fs module also includes functions that hide the opening and closing of directory resource handles for you. For example, you can create, rename, and delete directories:

await fsPromises.mkdir('sampleDir'); await fsPromises.mkdir('nested1/nested2/nested3', { recursive: true }); await fsPromises.rename('sampleDir', 'sampleDirRenamed'); await fsPromises.rmdir('sampleDirRenamed'); await fsPromises.rm('nested1', { recursive: true }); await fsPromises.rm('nested1', { recursive: true, force: true });

Examples 2, 5, and 6 demonstrate the recursive option, which is especially helpful if you don’t know if a path will exist before creating or deleting it.

There are two options to read the contents of a directory. By default, the readdir function returns a list of the names of all the files and folders directly below the requested directory.

You can pass the withFileTypes option to get a list of Dirent directory entry objects instead. These objects contain the name and type of each file system object in the requested directory. For example:

const files = await fsPromises.readdir('anotherDir'); for (const file in files) { console.log(file); } const dirents = await fsPromises.readdir('anotherDir', {withFileTypes: true}); for (const entry in dirents) { if (entry.isFile()) { console.log(`file name: ${entry.name}`); } else if (entry.isDirectory()) { console.log(`directory name: ${entry.name}`); } else if (entry.isSymbolicLink()) { console.log(`symbolic link name: ${entry.name}`); } }

The readdir function does not provide a recursive option to read the contents of sub-directories. You’ll have to write your own recursive function or rely on a third-party module like recursive-readdir]().

It’s time to close() the resource handle for this article. We have taken a thorough look at how to work with files, links, and directories using the Node.js fs module. File processing is available in Node.js out of the box, fully featured and ready to use.

Deploying a Node-based web app or website is the easy part. Making sure your Node instance continues to serve resources to your app is where things get tougher. If you’re interested in ensuring requests to the backend or third party services are successful, try LogRocket.

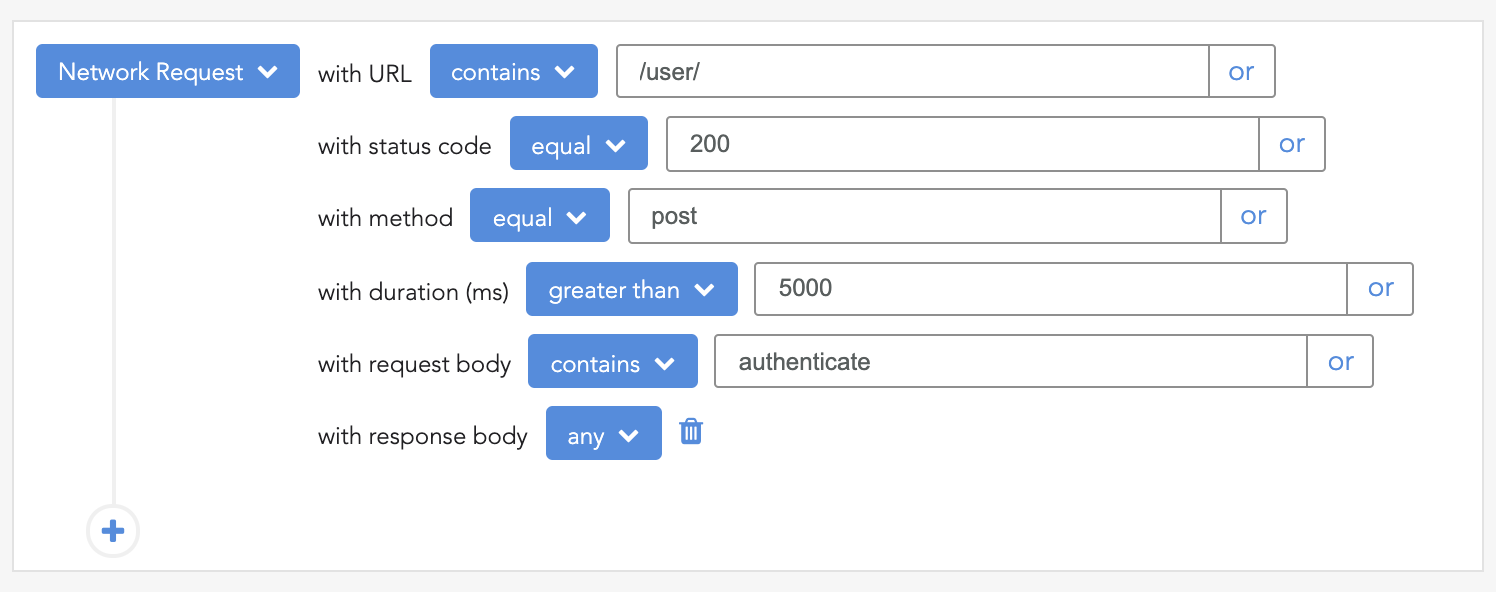

LogRocket is like a DVR for web and mobile apps, recording literally everything that happens while a user interacts with your app. Instead of guessing why problems happen, you can aggregate and report on problematic network requests to quickly understand the root cause.

LogRocket instruments your app to record baseline performance timings such as page load time, time to first byte, slow network requests, and also logs Redux, NgRx, and Vuex actions/state. Start monitoring for free.

Monitor failed and slow network requests in production

Monitor failed and slow network requests in production